Chromatography, a chef’s best friend?

As advances and new developments in chromatography allow the technique to become more precise, how is the technique enabling us to understand taste, and improve cooking?

When 32-time Michelin starred chef Joël Robuchon declared that, “cooking is chemistry, really,” he showed that he had an advanced understanding of the interactions and properties of compounds and their effect on taste. This was a perspective on cooking that flew in the face of many of France’s premier chefs, who preferred to see cooking as a fine art, beholden only to the creative genius of an artistic master and not the analytical mind of a chemist.

However, over the years many chefs, such as the UK’s Heston Blumenthal, have built careers treading the line between science and art. To them, the knowledge that cooking lies somewhere between the two has allowed them to employ the precise analytical mind and tools of a chemist, combined with the more creative aspects of an artist, to create food of unimaginable flavor and complexity.

Of course, many scientists would note that the creativity required to design studies and explore topics from new and inquisitive angles is often undervalued and appreciated by those outside scientific fields.

As science continues to develop and analytical techniques such as high-performance liquid-chromatography become more precise, how are these techniques being used to improve taste in the modern world?

How often do you sit down by the fire, hot chocolate in-hand, and think about all the science behind the creation of this classic winter staple? Never, you say? Well, now is the time.

Catching the charm of the chanterelle

A helpful tool in the armory of many chefs is the chanterelle mushroom. Its distinct, slightly bitter, taste profile combined with a light fruity aroma, make it a delicious individual ingredient, but its true value lies in the mushroom’s ability to enhance flavors of other ingredients – known as the kokumi effect.

The Kokumi effect does not refer to the creation of a distinct flavor such as bitter or salty but instead indicates the enhancement of existing ingredients to create a ‘rich’ or ‘rounded’ flavor for the entire dish.

To further study this effect, a team of researchers from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and the Leibniz-Institute for Food Systems Biology (both Munich, Germany) set out to clearly quantify the chanterelle-specific compounds that contribute to the effect [1].

Detailing the effort, lead author Verena Mittermeier (TUM) stated that by, “using the ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry method developed by our team, we are now the first to accurately quantify the key substances in chanterelles that are responsible for the kokumi effect” [2].

This sensitive ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography–differential ion mobility spectrometry–tandem mass spectrometry approach was able to identify natural substances derived from fatty acids involved in the effect. These included 14,15-dehydrocrepenynic acid and (9Z,15E)-14-oxooctadeca-9,15-dien-12-ynoic acid, as well as others that were identified as unique to the mushrooms.

Further storage experiments highlighted that different conditions impacted the composition of these derivatives, for instance, whether the chanterelles are stored whole or chopped.

The results of this study could be used to establish a quality control test for the mushrooms by identifying the levels of the chanterelle-specific derivatives. A further impact to the world of food science could be to use this information to improve the taste of other savory or mushroom-based dishes.

The miracle of the Maillard reaction

The miracle of the Maillard reaction

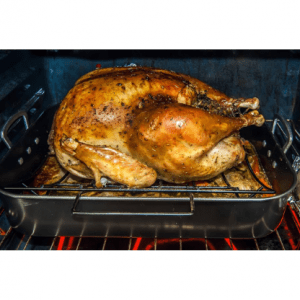

As a turkey roasts in the oven, what is actually happening to turn the skin golden brown and give the meat its delicious taste?

Analyzing alcohols

Key to the development of specialized flavors in some wines and spirits is the aging of the alcohol in an oak barrel, which releases compounds that influence the taste, aroma, color and mouth feel. Oak wood also releases compounds known as coumarins that are produced by many plants in an effort to fend off would-be predators.

It is not yet understood how these defensive chemicals may impact the taste profiles of the wines and spirits. A team of researchers from the University of Bordeaux (France), led by Axel Marchal, recently decided to find out [3].

Using liquid-chromatography high-resolution mass spectrometry, the team scanned oak wood extract for several different coumarins. This technique unveiled five established oak coumarins and a sixth, known as fratexin, which had never been found in oak wood.

Trained sensory judges were then enlisted to taste test the compounds. The previously established coumarins were determined by the panel of judges to be bitter, while the fratexin engendered a sour taste. Analyzing 90 red wines and 28 spirits for their coumarin concentration, the researchers determined the extent to which the compounds permeated into the beverages from the barrels.

Coumarins were found in their highest concentrations in spirits, followed by red and then white wines. This is likely the result of the length of time each beverage spends in the barrels, as the trend of increasing aging time – from white wine (the lowest) to spirits (the highest) – correlates with the increase in coumarin. However, a causal link has not yet been shown and there could also be a relationship between coumarin concentration and alcohol content.

Individually, the concentration of each coumarin was not high enough to affect human taste but a combination of all six added to non-oak-aged wines and spirits led the judges to note a distinct increase in bitter flavor. The team hope that these findings can be used to improve the taste of wines and spirits, with future studies potentially looking into the reduction of coumarin concentrations in barrels.

What’s in a hot chocolate?

What’s in a hot chocolate?