A hammer doesn’t need a nail

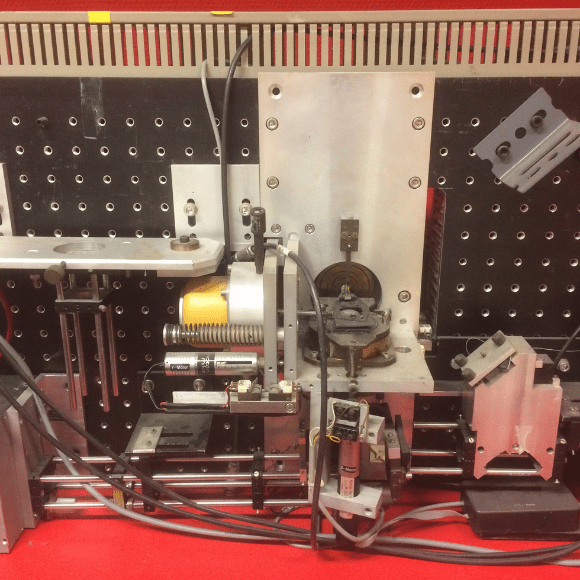

Who deserves more credit: the person that makes a hammer or the person that uses it to hit a nail in the wall? I recall the lively discussion of this question between two professors (now both emeritus) of our department. One of the professors was Fred Brakenhoff, who was among the first to build a confocal microscope (i.e., the maker of the hammer) [1]. The other professor was Nanne Nanninga, who used microscopes to study bacterial anatomy (a.k.a., the user of the hammer) [2].

My (easy) way out would be to answer that we need both. A new tool is more likely to be adopted if it is applied to solve a pressing problem. That is the reason that PCR, GFP and CRISPR–Cas9 are so famous that I don’t need to explain their abbreviation. These technologies open new possibilities and they deserve(d) a Nobel Prize because of their demonstrated use in research.

But the discussion about the hammer touches upon another issue. Is the hammer by itself of interest? In other words, is a new technology relevant, if its application is not demonstrated and does it deserve publication? I do think so. We have published a number of papers ourselves with new or improved methods that do not solve an existing problem. In several of those, not even a real application was included. Some of the methods that we have developed have been of interest to many [3], others are hardly cited [4]. The latter paper reported a new quantification method for a bacterial molecule. It was actually based on a relatively old paper that was poorly cited [5]. This by itself shows that if papers are not well cited, they can still be of use. Moreover, papers with new or improved methods may be a source of inspiration, without being cited. One thing is certain, if a method is not published, no one will know about it.

Ideally, a new tool is reported in a paper that passes peer review, as peer reviewed publications are the gold standard in scientific publishing. To this end, it is important to have platforms that have a strong focus on publishing methods and new technologies, even when there is no application demonstrated. In general, I would like to see more options for papers that focus on new methods. Sure, there are a couple of journals with a strong focus on technology and methods, but the options are rather limited. Quite often, I get the advice to publish a methods paper in a (mega-)journal with a broad scope, but this is not necessarily the best platform. I think that tools deserve specialized journals, which makes them easier to find. That is why I am a fan of journals that show a strong interest in the development of novel techniques. Clearly, Biotechniques is such a journal and that is why I did not take long before accepting their invitation to contribute.

- DNA microarrays with Pat Brown

- Cryo-electron tomography with Ariane Briegel

- A peek behind the paper – David Saul and Jo Stanton on the new method for DNA extraction

I strongly believe in open access publishing and I find that peer review usually improves a paper. However, there are alternatives. Let me explain this with a personal experience. When developing new methods for (cell) biology, we often are criticized for not showing any biological or physiological relevant experiments. Demonstrating the new tool is useful in a cellular context is not enough. Perhaps I’ve just been sending the manuscripts to the wrong journals. But, as I stressed above, it is important to get your work out there. This turned out to be extremely difficult in the case of a project that was part of my post-doc. We reported the synthesis of a photo-activatable lipid and showed that it can be used in cells. We failed to get it through peer review (believe me, we tried hard). Last year I decided to publish the work as a preprint [6]. Only weeks later, I was contacted by someone that wanted to use the compound. For me, this was the ultimate reward. It proves that publishing new methods, tools or technologies, regardless of the platform, is valuable and that others can benefit from it.

Let’s keep on developing methods and technologies, even if the application is not obvious. New technologies, new methods and new tools will be key to break the boundaries of what is currently possible and that is a core business of science. It is equally important to publish results. It may inspire others to make the method easier, cheaper or better. And you may be surprised to learn that a seemingly useless hammer eventually is applied in some unforeseen way.