No rejections for new islet transplantation method

A nonhuman primate preclinical study shows great potential for a new treatment of type 1 diabetes.

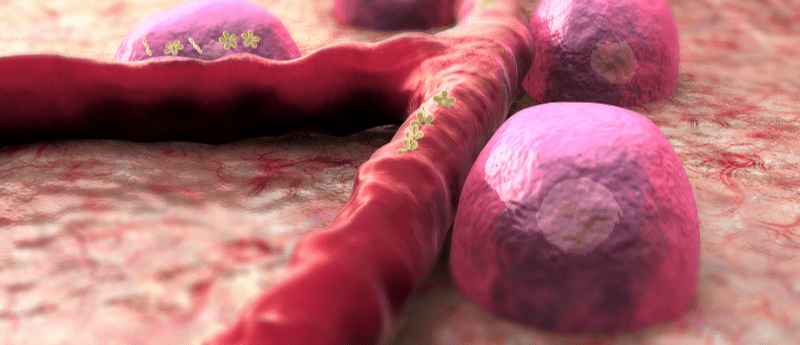

For those with type 1 diabetes, lifelong daily insulin treatments are the norm. However, an alternative treatment option in the form of islet transplantation is also a possibility. Islets are a group of pancreatic cells that contain insulin-producing beta cells, which are attacked as part of an autoimmune response in those with type 1 diabetes. Islet transplants are at risk of rejection by the body, so those who have this alternative treatment method also have to take lifelong immunosuppression drugs.

Now, a team of researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Harvard Medical School (both MA, USA), in collaboration with scientists at the Georgia Institute of Technology (GA, USA) and the University of Missouri (MO, USA), has developed a novel biomaterial that, when combined with islets at the point of transplantation, can prevent rejection. This removes the need for long-term immunosuppression.

In the preclinical study, the biomaterial, which consists of a protein called SA-FasL (an immune tolerance promoter) attached to the surface of microgel beads, and islet mixture was transplanted into nonhuman primate models with type 1 diabetes. The animal models were then also given an anti-rejection drug for 3 months.

“Our strategy to create a local immune-privileged environment allowed islets to survive without long-term immunosuppression and achieved robust blood glucose control in all diabetic nonhuman primates during a six-month study period,” explains lead author Ji Lei (MGH/Harvard Medical School).

Extracellular vesicles found to drive extracellular communications

Extracellular vesicles found to drive extracellular communications

Extracellular vesicles were once thought to be nothing more than cellular debris, but now researchers find they may drive extracellular RNA-based communications.

“We believe that our approach allows the transplants to survive and control diabetes for much longer than six months without anti-rejection drugs because surgical removal of the transplanted tissue at the end of the study resulted in all animals promptly returning to a diabetic state.”

A unique and beneficial feature of the transplantation method included embedding the biomaterial/islet combination into a bioengineered pouch formed by the omentum – a fold of fatty tissue that hangs from the stomach and covers the intestines.

“Unlike the liver, the omentum is a non-vital organ, allowing its removal should undesired complications be encountered,” Lei continues. “Thus, the omentum is a safer location for transplants to treat diabetes and may be particularly well suited for stem-cell-derived beta cells and bio-engineered cells.”

The team are now looking to move into clinical trials and are excited about the positive results from the highly relevant preclinical nonhuman primate model, as co-corresponding author James F. Markmann (MGH) explains: “This localized immunomodulatory strategy succeeded without long-term immunosuppression and shows great potential for application to type 1 diabetes patients.”