The mummy returns: Egyptian priest Nesyamun ‘speaks’ for the first time in 3000 years

According to Ancient Egyptian beliefs, “to speak the name of the dead is to make them live again.” Utilizing the latest in 3D printing technology, modern-day researchers have taken it one step further, allowing the dead to speak for themselves by recreating the vocal cords of the long deceased.

Over 3000 years ago, Nesyamun was living as a priest and a scribe at the temple of Amun in the Karnak complex at Thebes (modern-day Luxor, Egypt). In such a role, his voice would have been essential for performing ritual duties with both spoken and sung elements. Upon his death, thought to be due to a severe allergic reaction in his late 50s, his body was preserved and entombed, ready for the afterlife.

In 1823, the remains and ornate coffin of Nesyamun were discovered and moved to the Leeds City Museum (West Yorkshire, UK) where they have resided since. Thought to be one of the best-preserved mummies, the study of Nesyamun’s coffin has taught archeologists a great deal about life during that historical period and explained much of Ancient Egyptian culture.

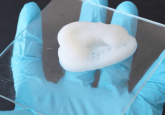

Nearly 200 years after the discovery of his tomb, the remains of Nesyamun are in the spotlight once again as researchers recreate his vocal cords as a 3D-printed Vocal Tract Organ model, in an attempt to see what it meant to talk like an Egyptian.

The Vocal Tract Organ system was first demonstrated by David Howard (Royal Holloway, London, UK) in 2013, initially developed for use by those who have lost normal speech function due to damage to the vocal tract. Howard was later approached by archeologist John Schofield (University of York, UK) who proposed the archaeological and heritage potential for this technology.

Following a CT scan of Nesyamun at Leeds General Infirmary, the team studying the mummy discovered that the soft tissue of his vocal tract was virtually intact, an unusual feature in such an ancient relic, making him perfect for this technique. Using measurements taken from the CT images, they created a 3D-printed vocal tract that was an exact replica of the mummy’s unique vocal organs.

This Vocal Tract Organ was combined with an artificial larynx sound, something commonly used in modern-day speech synthesis systems, and produced the opportunity to hear the vocal tract output of the long diseased.

- Ötzi the ancient iceman provides insight into the modern microbiome

- Mummy helps unwrap smallpox

- Can modern DNA sequencing solve history’s greatest murder mystery?

Unsurprisingly, the mummy didn’t have much to say and the researchers were only able to produce a vowel-like sound from the printed organ. The researchers stated that the sound is a “fundamental frequency” of Nesyamun’s voice and determining the exact tone of how his voice would have sounded could have been complicated by the burial position of the head and deterioration over time.

Previous work on recreating voices has been based on approximations, utilizing animated facial reconstruction software. This is the first time that researchers have been able to use the exact anatomical structure of the individual whose voice they were trying to recreate.

As with any research that involves human tissue, ethical concerns are raised if no consent is given, even when the subject (and all of their next of kin) are long dead. However, inscriptions on the coffin of Nesyamun suggested he hoped to speak again and “to address the gods as he had in his working life.” The research group state that they are “fulfilling his declared wishes,” and in doing so are allowing him to live forever.

The research was recently published in Scientific Reports, with the authors giving a full history of Nesyamun’s life, both pre- and post-death.

“Ultimately, this innovative interdisciplinary collaboration has given us the unique opportunity to hear the sound of someone long dead by virtue of their soft tissue preservation combined with new developments in technology,” commented the paper’s co-author Joann Fletcher (University of York).

“So given Nesyamun’s stated desire to have his voice heard in the afterlife in order to live forever, the fullfilment of his beliefs through the recreation of his voice allows us to make direct contact with ancient Egypt by listening to a voice that has not been heard for over 3,000 years, preserved through mummification and now restored through this pioneering new technique,” Fletcher concluded.