The untapped potential of ultrasound

Researchers hope life-changing deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease may become accessible to more people by switching implanted electrodes with a wireless external device and ultrasound.

Ultrasound has been used for imaging since the 50s and is used in physiotherapy to stimulate deep tissue healing. Recently scientists at the Salk Institute (CA, USA) have been investigating ultrasound to treat other diseases, taking advantage of the safety and penetrating abilities by engineering cells to be sensitive to ultrasound frequencies. The group has managed to activate mammalian cells using ultrasound frequencies, giving hope for wireless deep brain stimulation to treat symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

Parkinson’s is a neurological disorder that affects movement. It often starts with a tremor in one hand and develops gradually until daily activities become challenging. Treatment options include drugs or, in some advanced cases, deep brain stimulation, which relieves symptoms by producing counter impulses to regulate the abnormal impulses caused by the disease. It involves implanting a pacemaker-like device into the brain, creating artificial electric impulses that activate mammalian cells.

Ultrasound for ultra-precise drug delivery

A combination of lipid vesicles and ultrasound waves can provide highly specific drug delivery to target sites in rat brains.

Researchers hope to achieve a deep brain stimulation effect without implanting electrodes into the brain using ‘sonogenetics’. First described by Sreekanth Chalasani, sonogenetics uses ultrasound waves to stimulate genetically marked cells safely. The group previously found a protein (TRP-4) that makes cells very sensitive to safe frequencies of ultrasound. They hoped to activate mammalian cells deep in the brain, mimicking deep brain stimulation. However, complications arose when researchers tried to add TRP-4 onto mammalian cells.

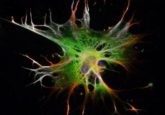

In this study, the team trawled through 300 proteins to find one that would create ultrasound stimulation in mammalian cells. After a year of testing the effect of each protein on a cell line known not to respond to ultrasound frequencies, researchers found a protein (TRPA1) that allowed for the desired response in the cells. “We were really surprised,” commented co-first author Marc Duque. “TRPA1 has been well-studied in the literature but hasn’t been described as a classical mechanosensitive protein that you’d expect to respond to ultrasound.”

It’s very promising that mammalian cells presenting TRPA-1 are stimulated using ultrasound. However, the next roadblock lies in a delivery method for gene therapy that can cross the blood-brain barrier. With more discovery needed before using sonogenetics for Parkinson’s, researchers are looking to the heart and hope to use sonogentics to replace the pacemaker with an external device soon. But for now, this group of researchers is focused on understanding the mechanisms involved and enhancing sensitivity.