What’s next… smart skin?

A group of researchers has developed a patch that imitates the texture and flexibility of human skin while containing artificial intelligence (AI) technology that records health data.

Researchers from the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (IL, USA) have recently created a computing device that can be stuck to the skin to monitor one’s health. This wearable technology has the potential to offer personal monitoring of complex health data, such as oxygen, metabolites, sugar and immune molecule levels in the blood.

Senior author, Sihong Wang reported, “With this work we’ve bridged wearable technology with artificial intelligence and machine learning to create a powerful device which can analyze health data right on our own bodies.”

By making advanced health data accessible to the individual, disease indicators may be flagged by the wearable device before symptom onset. This would allow for earlier detection and treatment, potentially mitigating the impact of the disease. However, to be capable of this, these AI devices must be flexible and easy to wear on the skin with the ability to learn a person’s health history, creating a complex health profile that can recognize signs of disease. Smart phones and smart watches lack the complex analysis needed to create such a detailed health profile.

Under the sea? How coral reef health monitoring may come ashore

Under the sea? How coral reef health monitoring may come ashore

A new AI method that can accurately detect coral reef health through sound recordings may remove the need for intensive visual studies by expert divers.

“With a smart watch, there’s always a gap. We wanted something that can achieve very intimate contact and accommodate the movement of skin,” commented Wang. The research team aimed to create a small, artificially intelligent chip that could synthesize health data gathered from biosensors into a coherent health profile.

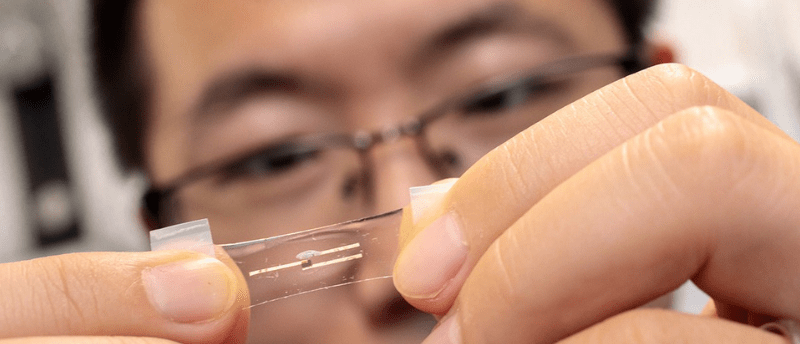

To achieve this, the researchers built semiconductors and electrochemical transistors out of polymers with high flexibility. They then used these polymers to construct an AI chip, or a neuromorphic computing chip. This chip can collect and analyze the health data rather than just collecting, which would require an additional machine to analyze the data. Having to transfer the large amounts of data to another machine would be slower and pose threats to health privacy.

The research team tested their chip using electrocardiogram (ECG) data. By training the device to classify ECGs into healthy activity and four different types of abnormal activity, the team could assess whether the device could accurately classify unknown ECG data. The chip, regardless of how much it was contorted, could correctly classify the heart activity.

Wang and his team recognize the need for further development of the chip for deducing health patterns, but the initial results contribute positively to creating a wearable complex health tracker. In future, they think that these devices may be able to send health updates to clinicians or independently monitor and alter medications. Wang commented, “If you can get real-time information on blood pressure, for instance, this device could very intelligently make decisions about when to adjust the patient’s blood pressure medication levels.”