How can we treat cancer-related cachexia?

The exercise hormone irisin may be responsible for muscle weakening in cancer-related cachexia, but only in males.

A new study from the Indiana University School of Medicine (IN, USA) has demonstrated that knocking out the precursor of irisin, the exercise hormone, in mouse models of cancer has sex-dependent, protective effects against cachexia. This research was presented at the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research‘s annual meeting (9–12 September 2022; Austin, TX, USA).

Cachexia is the weakness associated with severe illnesses and poses a major threat to individuals with cancer. It causes weight loss, inflammation, anemia and intense fatigue in addition to numerous other life-threatening symptoms. According to the National Cancer Institute (MD, USA), there are currently no approved treatments for cachexia caused by cancer in the United States.

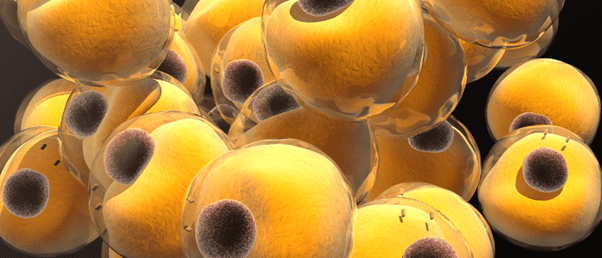

In cachexia, white adipose cells that store fat get turned into brown adipose cells that burn fat and produce heat. The researchers focused on this particular feature of cachexia to investigate possible treatments. They looked to irisin, a hormone often produced during exercise and is known to facilitate the transformation of white adipose cells to brown adipose cells in healthy individuals.

The study utilized mutant mice with the protein-coding gene fibronectin type III domain-containing protein 5 (FNDC5) knocked out, which is the precursor of irisin. This means that the mutant mice could not produce irisin and were, therefore, unable to create fat-burning cells. They were then implanted with metastatic MC38 colorectal cancer or Lewis Lung Carcinoma cells. These were compared with control mice that were also implanted with cancerous cells but could still produce irisin.

How did mucus evolve to be so slimy?

How did mucus evolve to be so slimy?

A study of mucins, a protein in mucus that gives it its characteristic slimy properties, gives insight into how novel gene function evolves.

All of the mice developed tumors; however, the male knockout mice showed no loss of muscle mass or body weight, indicating that they did not develop cachexia. They exhibited normal mobility and activity compared to the control mice that did exhibit signs of cachexia, demonstrating that irisin does play some kind of role in the development of muscle weakness and atrophy. Importantly, female knockout mice did show signs of cachexia suggesting there is more to the story than just irisin.

Researchers also measured higher levels of UCP1, a gene involved in creating brown adipose cells, in the control mice than in healthy mice with no tumors. By contrast, the knockout mice and the healthy mice showed similar UCP1 levels.

Finally, the researchers investigated what effect tumor development had on pro-atrophic pathways in skeletal muscle, such as STAT3 phosphorylation, Atrogin1 and Murf1 expression. These pathways remained stable in the knockout mice, as they do in healthy mice. The knockout mice, regardless of sex, were not protected against bone loss, indicating that any positive effect of blocking irisin was targeted to the muscles.

The study demonstrates that irisin, or its precursor FNDC5, has an important role in muscle weakening in male mice. However, further research is necessary to understand why female knockout mice were not protected from developing muscle weakness and cachexia.