Autophagy: controlling crisis

Results of a recent study show that autophagy prevents the proliferation of cells in crisis, which can lead to cancer, dismissing the previously accepted theory that autophagy promotes cancer formation.

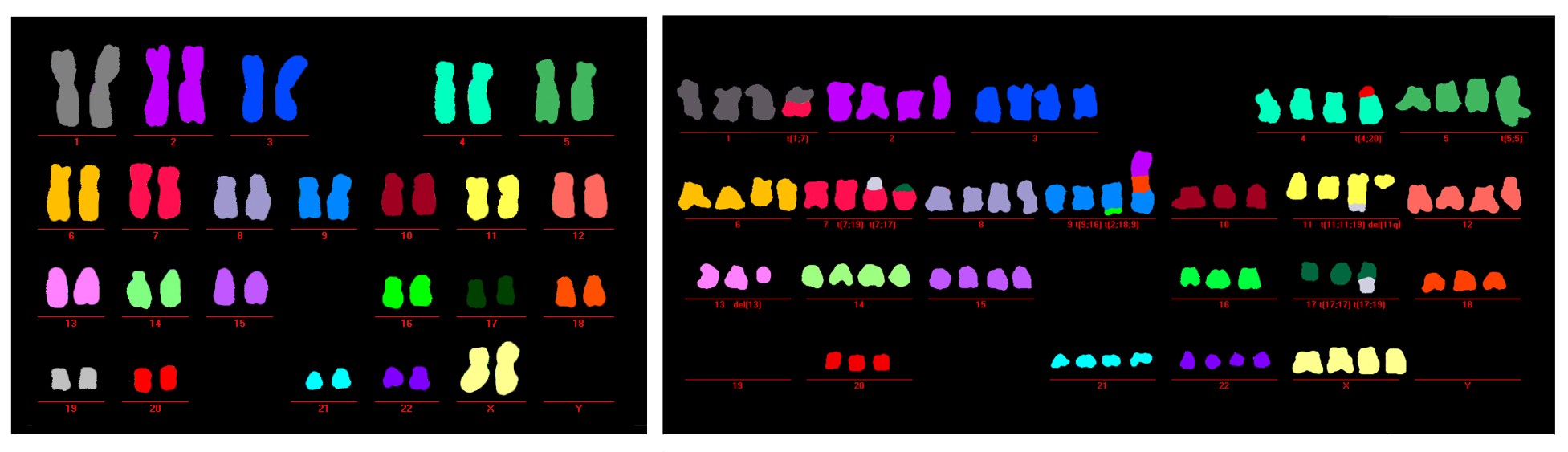

Left: Ordered healthy chromosomes in cells with functioning autophagy. Right: Disordered malformed chromosomes in a cell in crisis with deregulated autophagy. Credit: Salk Institute (CA, USA).

Autophagy, a cellular recycling process that has previously been considered to assist cancer growth, has recently been shown to play a vital role in preventing the survival of pre-cancer cells. These findings are the results of a study by a research team from the Salk Institute, led by Jan Karlsender, and could have serious implications for current and future cancer therapies.

Karlsender’s team were studying a cellular state known as ‘crisis’ during which the chromosomes in cells begin to fuse and become dysfunctional leading to widespread cell death or, if it is not controlled, cancer. Crisis occurs when the telomeres at the end of chromosomes become too short to defend them from fusion and the cell resists signals to halt all proliferation due to the action of faulty tumor suppressor genes (TSGs).

To study the cell death that should result from crisis, the researchers induced crises in a line of human cells by disabling various TSGs and compared them to normally dividing cells. Observing morphological and biochemical markers of apoptosis and autophagy in the two cell lines they were able to identify that, while both processes were responsible for the low-level cell death in normal cells, autophagy was by far the more prevalent cause of cell death in the cell line experiencing crisis.

Following up on this finding Karlsender inhibited autophagy in the crisis cells and observed their response. The cells continued to proliferate out of control and their chromosomes became severely disfigured, mirroring those of cancer cells.

“These results were a complete surprise,” exclaimed Karlsender. “There are many checkpoints that prevent cells from dividing out of control and becoming cancerous, but we did not expect autophagy to be one of them.”

Finally, the research team studied the effect different types of DNA damage had on which cell death pathway was stimulated. Taking the normal cell line, DNA damage was inflicted either in the center of the chromosomes or at the ends, in the telomeres. The results showed that DNA damage in the center of chromosomes stimulated apoptosis, while telomere damage led primarily to autophagy.

Extensive evidence exists to suggest that once cells become fully cancerous, autophagy is manipulated to fuel their growth by cannibalizing other cells to obtain vital materials. As a result, it has been largely assumed that autophagy was also an assistant to cancer formation from pre-cancerous cells. The results of this study, however, directly contradict this hypothesis and suggest that treatments designed to silence autophagy in an attempt to starve cancer may actually be helping to promote its growth.

“This work is exciting because it represents so many completely novel discoveries. We didn’t know it was possible for cells to survive crisis; we didn’t know autophagy is involved with the cell death in crisis; we certainly didn’t know how autophagy prevents the accumulation of genetic damage. This opens up a completely new field of research we are eager to pursue,” explained Karlsender.

The next step for the research is to examine the differences in cellular response to the location of DNA damage, to try to explain why damage in the telomeres leads to autophagy while damage to the center of the chromosome leads to apoptosis.