Cancer disparities: shifting the scales on underrepresentation in science

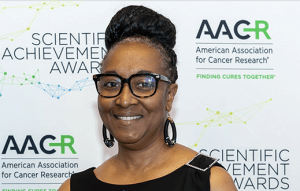

Camille Ragin (left) is the Associate Director for Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Accessibility and a Professor in the Cancer Prevention and Control program at Fox Chase Cancer Center (PA, USA). Over the last 2 decades, Camille’s tireless work mentoring scientists from underrepresented backgrounds, combined with her research into the disparities found in cancer have built up to constitute an impressive corpus of work, for which she was recently awarded the AACR-Minorities in Cancer Research Jane Cooke Wright Lectureship.

Camille Ragin (left) is the Associate Director for Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Accessibility and a Professor in the Cancer Prevention and Control program at Fox Chase Cancer Center (PA, USA). Over the last 2 decades, Camille’s tireless work mentoring scientists from underrepresented backgrounds, combined with her research into the disparities found in cancer have built up to constitute an impressive corpus of work, for which she was recently awarded the AACR-Minorities in Cancer Research Jane Cooke Wright Lectureship.

In this interview, we speak to Camille about the motivations that drive her, her approaches to research and community engagement and the work of the African-Caribbean Cancer Consortium that she founded almost 20 years ago.

What is the focus of your research work?

My lab focuses on disparities in cancer, specifically evaluating how we can address disparities that impact Black populations around the world. I’m a molecular epidemiologist by training, so do a lot of population-based work, exploring different biomarkers and evaluating behaviors to establish better ways to assess risk and prevention.

What techniques do you use in your work?

The scope of my work is fairly broad, so there is a combination of community engagement work and laboratory-based research. From a community perspective, this involves a lot of survey questionnaire data collection, which we often combine with the collection of biospecimens to examine biological markers in different communities.

The biomarker analysis is what takes me into the lab. There, I look for genetic markers, specifically polymorphisms. I also explore genetic ancestry and what role it might play in cancer development or cancer outcomes for patients with cancer.

Could you tell us about the work for which you’ve been awarded the AACR-Minorities in Cancer Research Jane Cooke Wright Lectureship?

This particular award doesn’t just focus on the research I conduct, but also the contributions I have made with regard to mentoring and career development of other underrepresented minority scientists. In terms of my science, there are two spaces that I’m being recognized.

One of the efforts that is being recognized is my work on head and neck cancer. Looking at patients who are diagnosed with this disease, I’ve been able to identify a new ancestry-informative genetic marker that seems to be correlated with poor outcomes. What’s more, this marker appears to predominantly affect Black populations treated with platinum, or radiation, based therapy for head and neck cancer.

The second area that is being recognized, is the work that I’ve done with the African-Caribbean Cancer Consortium, which does research in three major geographic regions with large Black populations in the geographic regions – the U.S., the Caribbean and Africa. Then, as I mentioned, the mentoring of underrepresented students and scientists both locally in the U.S. and internationally.

Bringing the community closer to science in cancer research

Bringing the community closer to science in cancer research

Robert Winn and Katherine Tossas, the Cancer Center Director and the Scientific Director of Catchment Area Data Access and Alignment at Virginia Commonwealth University (VA, USA), discuss the importance of connecting the community with cancer research to improve understanding of non-biological factors that increase the likelihood of different cancers.

Having identified that polymorphism, are there any practical recommendations to patients or clinicians to help mitigate its impact?

At the moment, I think it’s a little too early to know what the alternative options are, but I’m currently funded by the NIH to dig a bit deeper to understand the effect of that particular polymorphism, especially in the context of drug response and the mechanism driving it. Once we understand this, we can help provide better information to help select the optimal treatment regimen for a patient with this polymorphism and even inform the development of novel therapeutic possibilities.

What approaches are you using to investigate the mechanisms driving the impact of this polymorphism?

I have had the opportunity to collaborate with other experts here at Fox Chase and around the U.S., for this project, making it a multidisciplinary effort. I’m collaborating with several basic scientists, including Robert Sobol (Brown University, RI, USA), who does a lot of the in vitro experiments designed to deliver an understanding of the mechanism behind this polymorphism and how it’s impacting the overexpression of a certain DNA repair gene, called polymerase beta.

Polymerase beta is a base excision repair gene responsible for repairing double-stranded DNA breaks. We believe that the action of this particular protein is overly expressed somewhat in patients that carry the polymorphism we identified. Dr. Sobol is doing experiments in cell lines to try to understand that mechanism.

I also have a PhD student, working with another colleague of mine here at Fox Chase, Eti Cukierman, who is an expert in the tumor microenvironment. My student is performing immunofluorescence assays to examine the localization of the protein in the nucleus or the mitochondria to try to understand the dynamics behind the protein’s action, which is impacted by this polymorphism. A lot of these experiments examine how the action of the protein changes under stress versus normal conditions in cells with this polymorphism. Together, all of these answers will help us to figure out what’s really happening within the cells of these patients.

Could you tell us more about your work with the African-Caribbean Cancer Consortium?

I established the consortium about 17 years ago when I was a postdoc. At the time when I was preparing to launch my career and looking for opportunities to work in my space, I recognized that there was limited research output from certain Black populations. This included African Americans or Black individuals here in the U.S., but I also noted that there was a limited amount of research output in the Caribbean and also in Africa when it comes to cancer. I also noted that there was a vast underrepresentation of Black populations in studies of cancer.

So, I decided to pull together a network of investigators who were interested in working in these spaces to provide an opportunity to collaborate to address the problem of underrepresentation. Since then, we have now grown to a huge network of over 200 investigators with networks in the U.S., the Caribbean – where members represent about 16 different countries – and Africa, where we have members from 11 African countries.

Our goal is to focus our collaborative work on studying cancer in populations of African ancestry from the full spectrum of community-engaged research to basic science research. We’re looking at many different cancer sites. So, it’s a team science approach to addressing disparities problems.

Interesting, a similar approach to Cancer Grand Challenges: looking to create links between international communities and disciplines in cancer research?

Absolutely it is! I chuckle when you say the Cancer Grant Challenge because when the call came out, I really wanted to go after this because this was a perfect model for it. It was just not the opportune time for me to write the application, but it certainly does mirror a Cancer Grand Challenge. We just don’t have the funding. That’s the challenge. That’s the difference.

What did you take away from some of the meet-and-greet workshop sessions at AACR 2024 regarding the current landscape facing minorities in cancer research?

I am very encouraged, especially from this meeting, by the mobilization and efforts underway to address cancer health disparities. With all of the interactions that I’ve had, the meet-and-greet, the minorities in cancer research, council activities, the professional development series – all of those activities really speak to this momentum that we’re gaining in addressing the science and building careers. Making sure we have a workforce equipped to address these disparities.

If you could go back and give yourself some advice at the very beginning of your career, what would it be?

Oh my goodness. Well, I would say that it has been a great ride so far. So I wouldn’t change much except for maybe paying a little bit more attention to work-life balance. It’s hard work, and I’m sure a lot of us in this space recognize that. I don’t regret any of it, but I do think that I needed to think a little bit more carefully about how to create a balance so I have some me time to allow me to rejuvenate and be ready to go again.

I’m grateful because I benefitted from great mentors who have really bought into my career and I’m appreciative of that because I think without it, I wouldn’t have been able to accomplish some of the things that I have. So, I don’t just give myself credit for my achievements. I’m standing on the shoulders of giants, and I appreciate that.