Cell-specific protein labeling clicks into place

A novel cell-specific method to identify proteins released by cells could lead to advancements in tracking diseases like cancer.

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute and Imperial College London (both in London, UK) utilized click chemistry, which was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry earlier this year, to develop a new method to study proteins released by cells. This method is able to identify proteins released by a specific type of cell, even in the midst of a myriad of other cell types, as is the case in the body.

Biomarkers are valuable tools that are used in research and in clinical practice to diagnose diseases from blood or tissue samples, for example. However, finding biomarkers is challenging as proteins that are uniquely made by diseased cells, and not released by healthy cells, need to be identified.

“When you have a sample containing various cell lines, it is very difficult to identify the proteins that came from a specific line. Of course, in the laboratory, we can create experiments with only one type of cell, however these conditions do not mirror what happens in the body where complex interactions between cells could affect their behavior and so the proteins they release,” explained Ben Schumann (Imperial College London), the senior author of the paper.

Who won the 2022 Nobel Prize in Chemistry?

Who won the 2022 Nobel Prize in Chemistry?

‘Click chemistry’ wins the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for its ability to simply and reliably synthesize complex molecules and its application in living cells utilizing bioorthogonal reactions.

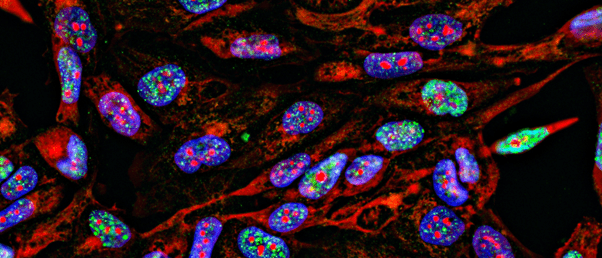

The researchers called this method Bio-Orthogonal Cell line-specific Tagging of Glycoproteins (BOCTAG), which involves adding chemical tags to sugar molecules that bind to a specific cell type. As all cells absorb sugar, the researchers needed to genetically modify the cell type of interest so that only this cell type adds the sugar to its proteins. The proteins that are then produced by these cells remain marked with the chemical tag, enabling the researchers to easily identify them.

The chemical tag that is bound to the sugar molecules is chosen because it can ‘click’ with another molecule in a highly selective manner, which means the researchers can isolate the desired protein or easily add a fluorescent tag to them.

The researchers showed that BOCTAG works in cell cultures with multiple cell lines, as well as in mice, by successfully tagging proteins from particular cancer cells. “In this study, we looked at proteins made by cancer cells, but our method could be used in other fields including immunology or the study of infectious disease,” said Anna Cioce (Francis Crick Institute), the first author of the study.

The research group will continue to develop their method, as well as use it to learn more about how cells produce different proteins depending on their environment.