MELK fails reproducibility tests

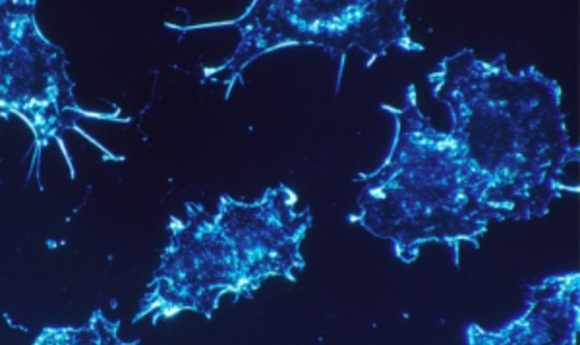

Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK) has previously been found to be overexpressed in many cancer cell lines. However, new research shows that MELK is not required for cancer growth.

Researchers at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (NY, USA) have found that the association between cancer and the maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK) is undermined by flawed scientific processes. Their report, published in eLife, suggests that MELK expression does correlate with tumor mitotic activity but is not required for cancer growth.

Lead author Jason Sheltzer believes their work is a good example of the scientific method, stating: “our study is a good illustration of the self-correcting nature of science.”

Sheltzer’s lab has been using genomic analysis to identify highly expressed genes in patients with cancers that have low survivability rates. They then utilized CRISPR to remove these genes in an attempt to kill the tumor cells. Like other labs they found that MELK was a candidate.

“Like other labs, we found that MELK tended to be very highly expressed in patients who did not survive very long,” Sheltzer said.

Based on the work of previous researchers, they attempted to use MELK as a positive control for their experiments. They were certain that when the MELK gene was removed, the tumor cells would be killed and they could be sure their technique was working.

“But, to our great surprise, the cancer cells didn’t die. They just didn’t care,” Sheltzer commented.

The team performed different tests to validate their methodology and finally concluded that the previous assumptions about MELK’s role in cancer had been wrong.

Sheltzer believes that off-target effects, such as RNA interference, may be responsible for generating this fundamental error.

“You think you’re knocking down one gene, but in reality those techniques are not very specific, so you’re also hitting a number of other different genes.”

Now the team plan to find other genes like the MELK gene using their CRISPR technique. “We think that this might be a common problem,” Sheltzer adds. “There are likely other genes like MELK out there and we’re going to use CRISPR to find them.”