Neutrons probe pancratistatin’s cancer-killing mechanism

Researchers investigate how pancratistatin, a cancer-fighting compound found in the Hawaiian spider lily, selectively targets cancer cells.

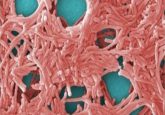

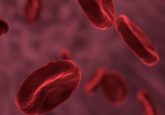

Pancratistatin is a compound found in spider lilies, a tropical plant native to Hawai’i, which kills cancer cells without harming healthy cells. This ability gives scientists hope that pancratistatin could lead to novel cancer treatments that can distinguish between healthy and cancerous cells, improving upon current treatments and reducing the risk of side effects. However, the mechanism through which pancratistatin selectively kills cancer cells has remained a mystery. Now, researchers at the University of Windsor (Canada) are utilizing neutron experiments performed at the US Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory (TN, USA) to understand how the compound achieves this.

Decades ago, scientists utilized living cells to discover that pancratistatin triggers apoptosis in cancerous testicular, breast, liver and nerve cells. Since then, researchers have relied on synthetic membranes, allowing them to study the compound without the variables that living systems bring.

“By experimenting with cellular extracts here at the lab, we’re building on previous work to get a more detailed picture for pancratistatin,” said Stuart Castillo, the doctoral candidate leading the study.

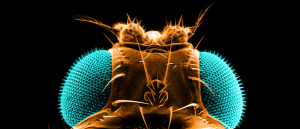

Mapping the larval fruit fly connectome

Mapping the larval fruit fly connectome

A new study has completely mapped the larval fruit fly brain for the first time, illuminating the positions of 3,016 neurons and how they connect.

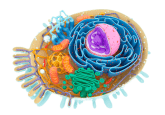

The mitochondria regulate many of the processes that are distorted in cancer cells. It is thought that cancer cells receive an influx of cholesterol, causing the mitochondria’s membranes to stiffen and stop communicating with other parts of the cell. This results in the uncontrolled multiplication of cells.

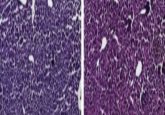

The researchers first showed that pancratistatin triggered apoptosis by stiffening synthetic mitochondrial membranes in a particular manner. They then utilized the Neutron Spin Echo spectrometer to observe cellular dynamics and compare how pancratistatin affects the inner and outer layers of the mitochondrial membrane in cancerous and noncancerous cells.

The Neutron Spin Echo spectrometer simultaneously records dynamics spatially and temporally, in Angstrom and microseconds respectively. Neutrons pass through biological material without damaging them, making them suitable for studying biological membranes.

“We’re looking specifically at how stiff the membrane is, how thick it is and how those molecules behave next to each other,” said Dominik Dziura, a co-author of the study. “The thought is that a healthy membrane will be flexible and move like it’s supposed to, binding to other receptors and membranes and allowing communication between cells, unlike cancerous membranes.”

The researchers hope their mechanistic insight will lead to novel non-invasive cancer treatments that don’t damage healthy cells.