On the wire: earlier cancer detection

A magnetic wire has been developed that can capture cancer cells and has promise to detect cancer sooner.

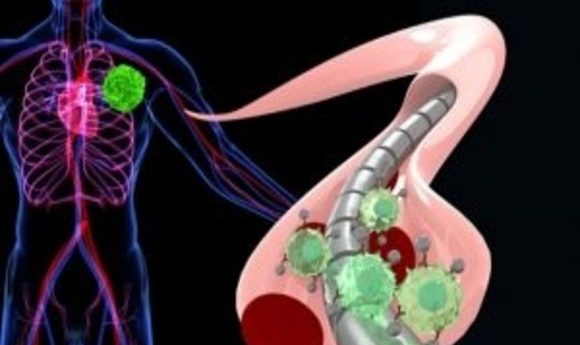

Green tumor cells that are bound to silver nanoparticles are picked up by the magnetic wire. Credit: Sanjiv Gambhir

Researchers from Stanford University School of Medicine (CA, USA) have developed a magnetic wire that can capture tumor cells in the blood, which could be utilized to diagnose cancers earlier.

Engineered magnetic nanoparticles are introduced that attach specifically to the free-moving cancerous tumor cells in the blood. This magnetizes the cancer cells and enables them to be picked up by the magnetic wire. It is hoped the wire could be inserted into a vein in a person’s arm and be a better option for diagnosing cancer than biopsies.

So far, it has only been demonstrated in pigs. However, this technique has already shown promising results, attracting 10–80-times more tumor cells than current detection methods in the blood. Fewer cells circulating in the blood mean the presence of cancer cells can often be missed, so this increased pick-up of tumor cells means that cancer could be detected even earlier than currently possible. It may also lead to the ability of doctors to easily track the progress of a patient’s response to treatments.

“These circulating tumor cells are so few that if you just take a regular blood sample, those test tubes likely won’t even have a single circulating tumor cell in them,” explained senior author, Sanjiv Gambhir. “So doctors end up saying ‘okay, nothing’s there.’”

Although the technique is still in the early stages of development for use in cancer cell detection, Gambhir believes there may be the potential to translate it to other diseases, too.

“It could be useful in any other disease in which there are cells or molecules of interest in the blood,” commented Gambhir, professor and chair of radiology and director of the Canary Center at Stanford for Cancer Early Detection.

“For example, let’s say you’re checking for a bacterial infection, circulating tumor DNA or rare cells that are responsible for inflammation – in any of these scenarios, the wire and nanoparticles help to enrich the signal, and therefore detect the disease or infection.”

The next steps for Gambhir and his team are to file for approval from the US FDA and hopefully replicate the successful results from the pig trials in humans.