RAS gene mutations fuel malignancy through crosstalk with tumor microenvironment

A single oncogenic mutation can hijack mechanisms causing benign tumors to become malignant.

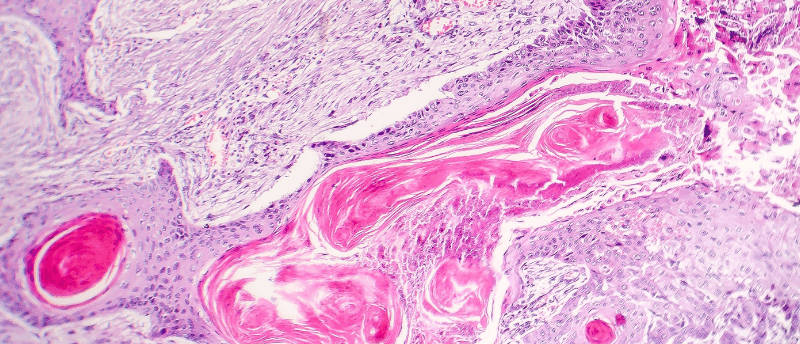

A study by researchers at Rockefeller University (NY, USA) finds that a single mutated gene in cancer stem cells can set in motion the transition from a benign to a malignant tumor in a common skin cancer. This causes an increasingly deviant feedback loop between cancerous stem cells and the surrounding tissue, leading to metastatic cancer. If this is the case in a variety of cancers, this finding could lead to a novel treatment approach.

Previously, it was not known if a couple of mutant cells cause healthy tissue to become cancerous, if diseased tissue leads to cancerous cells, or if it is a back-and-forth between the two. “It’s not just that cancer molds the microenvironment, or that the environment affects the tumor,” said Shaopeng Yuan, the first author of the study. “Our study shows that there is crosstalk between the microenvironment and the stem cells in tumors. They communicate with each other and create a loop of tumor-promoting factors.”

A small subset of cancer stem cells is responsible for keeping tumors alive and are key in the process of tumors becoming malignant. These cancer stem cells are resistant to chemotherapy and immunotherapy. A mutated RAS gene is found in some types of cancer including skin, pancreatic, lung and colorectal cancer. This mutation enables tissue stem cells to ignore the normal environmental signals and deviate from their usual mechanisms, thereby promoting uncontrolled tissue growth.

Could senescent tumor cells offer a new cancer vaccine strategy?

Could senescent tumor cells offer a new cancer vaccine strategy?

Researchers have found that senescent tumor cells induce a bigger adaptive immune response and can prevent tumors, which could lead to a senescent cell cancer vaccine.

The research group studied squamous cell carcinoma, a skin cancer that has been linked to RAS mutations, to understand the mechanism behind stem cells ignoring environmental signals. To do so, a mutant HRAS (a member of the RAS family most common in skin cancers) was induced in individual skin stem cells. The researchers monitored how these cancerous stem cells interact with the surrounding tissue using techniques including fluorescence imaging and fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

“Over time, the dialogue between the cancer stem cell and its microenvironment became more and more aberrant,” said Elaine Fuchs, the senior author. “As we deciphered the dialogue, we realized that the miscommunication between the stem cells and its microenvironment resulted in the activation of much the same pathway that is active in the corresponding human cancers that harbor a high mutational burden.”

This observation suggests that mutations affirm a pre-existing malignant progression that has already been initiated by aberrant crosstalk between cancer stem cells and the microenvironment.

Unexpected expression of the leptin receptor

The team then investigated how cancer stem cells change in this self-imposed malignant tumor microenvironment using scRNA-seq Smart-seq2 analysis and ATAC-seq (assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with high-throughput sequencing). The cancer stem cells started expressing the leptin receptor called Lepr. Leptin is a hormone produced by fat cells and is linked to obesity, so was unexpected in non-obese mice with non-fatty tumors. Lepr is rarely present in benign tumor cells and is not expressed in normal epithelium.

Using CRISPR, the researchers showed that Lepr and leptin receptor signaling was essential for the progression of benign tumors to a malignant state. They observed that the more leptin was present, the faster the tumor grew.

There was no apparent increase in fat cells and the benign growth, advanced tumor cells and the tumor microenvironment did not appear to express the leptin gene. This left the researchers wondering where the leptin was coming from.

Fine-tuning synthetic protein production with CRISPR

Fine-tuning synthetic protein production with CRISPR

Researchers at MIT have developed a novel method for controlling the precise amount of protein produced by mammalian cells, which could improve the production of specialized monoclonal antibodies.

The study found that leptin, which normally circulates in the bloodstream, is transported to the tumor through blood vessels that also provide nutrients. They also found that Lepr/leptin signaling within cancer stem cells stimulated many pathways that are hyperactive in cancers, such as the PI3-kinase, AKT and mTOR pathways.

“The leptin receptor/leptin crosstalk between cancer stem cells and the microenvironment drives a positive feedback loop that fuels malignancy,” said Yuan. “If we block this loop, which is a major pathway driving tumor progression, perhaps we can block tumor progression.” The researchers are now investigating ways of blocking the leptin receptor.

Yuan explained, “we are always looking for mutations, but we must not forget to think about how to stop signaling pathways that drive tumor growth.” If this mechanism is also present in other cancers, these findings could have implications beyond squamous cell carcinomas and lead to novel treatment approaches.