Inflammatory cell reversion: plastic surgery to be replaced as the primary treatment for ulcers?

Researchers have successfully converted ulcers into healthy skin in a mouse model study, by reprogramming skin cells to stem-cell-like keratinocytes.

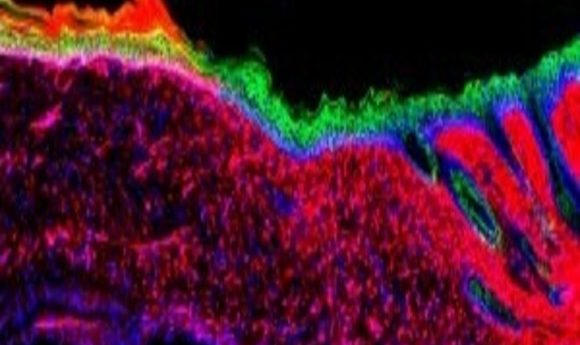

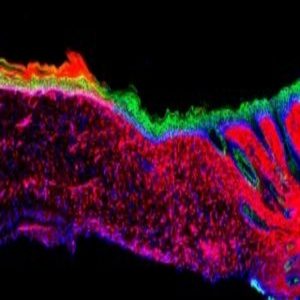

A cross-section of an ulcer treated with the AAV-based in vivo reprogramming technique, displaying the transformation of inflammatory wound cells (red) into epithelial cells (green). Credit: Salk Institute.

In research recently conducted at the Salk Institute (CA, USA), scientists have identified a process capable of converting inflammatory and wound repair cells into basal keratinocytes in the skin of mice. Primarily, the research provides a possible method of treatment for cutaneous ulcers that converts the ulcer into healthy skin, without the need for plastic surgery.

Senior author, Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, and first author, Masakazu Kurita, had previously identified that the transplantation of basal keratinocytes, the cells responsible for the generation of the diverse array of skin cells required for healthy organ function, was a vital aspect in the treatment of a cutaneous wound.

With this in mind, the researchers set out to identify if it was possible to bypass the transplantation process and directly convert the inflammatory mesenchymal cells into basal keratinocytes.

“We set out to make skin where there was no skin to start with,” remarked Kurita.

After initially identifying 55 possible reprogramming factors, consisting of proteins and RNA molecules that characterized basal keratinocytes, they conducted a series of experiments to narrow down this list to four specific factors. These factors could then be utilized to reprogram wound cells to the required keratinocytes in a process termed ‘AAV-based in vivo reprogramming’.

Testing this technique on the skin ulcers of mice, Kurita, Belmonte and colleagues observed a regeneration of healthy epithelia in just 18 days, which later went on to fuse with the tissue adjacent to the ulcer. Further genetic and cellular tests at the 3- and 6-month stages of the trial confirmed that the adapted cells were functioning as healthy skin cells.

Whilst Kurita admitted that before the technique could be trialed on humans, “we have to do more studies on the long-term safety of our approach and enhance the efficiency as much as possible,” the potential implications of this research are far-reaching.

“This knowledge might not only be useful for enhancing skin repair but could also serve to guide in vivo regenerative strategies in other human pathological situations, as well as during aging, in which tissue repair is impaired,” he concluded. If this does prove to be the case, then the future of regenerative medicine looks bright.