The genetics of parthenogenesis

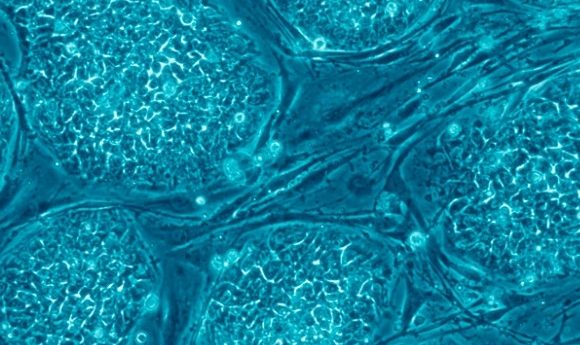

Researchers have identified five genes that can induce development of the three stem cell types of early stage embryos, potentially leading to the creation of a human embryo without the need for sperm or egg cells.

The reprogramming ability of skin cells was first demonstrated in 2006 with the introduction of the induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC). By expressing four of the central embryonic genes, researchers were able to transform the cells into early embryonic cells with the capability to generate an entire fetus.

Now, researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (Israel) have taken it one step further and, in addition to the fetus-producing iPSCs, they have transformed the cells into placental stem cells and stem cells that are needed for the development of other extra-embryonic tissues such as the umbilical cord, an extra ability that previous iPSCs lacked. Transformation from skin cell into one of these three early embryonic cell types takes about 1 month.

Using new technologies, the researchers were able to observe and analyze the molecular forces that control cellular fate decisions and reprogramming, as well as the basis of embryonic development. One discovery they made was that the gene Eomes controls the placental cell identity and development, whereas the Esrrb gene is responsible for fetal stem cell development.

-

Cellular organization in embryonic development: it’s all in the concentration

-

Natural selection in utero

-

Have you ever wondered how an embryo forms?

Five genes were identified that were needed for transforming skin cells into the embryonic cells and the team analyzed alterations and changes in genome structure and function inside the cell once the genes were added. The results, recently published in Cell Stem Cell, found that the cells first lose their individual identity and then, based on levels of two of the five genes, acquired the identity of one of the three cell types.

Past attempts have been made to develop a mouse embryo without the use of sperm or egg cells, though they have since required the use of cell types derived from a live embryo. The findings from this study demonstrate that there may be no need to kill an existing embryo to create one in a test tube.

The discovery has many implications for future research including improving the ability to model embryonic defects and placental dysfunctions. It also holds potential for solving infertility problems, allowing for the growth of a human embryo without the need for two separate gametes.