Extracellular vesicles found to drive extracellular communications

Tiny nano-sized bubbles called extracellular vesicles could answer the unsolved mystery of how cells communicate with each other.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) were once thought to be nothing more than cellular debris, but research has previously found that they play a role in mediating intercellular communication. Now, a team of researchers from Rutgers University (NJ, USA) have studied EVs using roundworms, Caenorhabditis elegans, and found they may also drive extracellular RNA-based communications.

EVs are excreted by cells and are nano-sized bubbles that carry bioactive cargo, which directs the development and differentiation of cells, among other functions. However, these nano-sized bubbles can also carry toxic cargo, including unfolded proteins in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

EVs could be beneficial in a variety of medical applications including improved drug delivery to treat inflammatory conditions. Additionally, as healthy and damaged cells package different EV cargo and can be found in the urine and blood, they could be used as biomarkers in liquid biopsies.

“Although EVs are of profound medical importance, the field lacks a basic understanding of how EVs form, what cargo is packaged in different types of EVs originating from [the] same or different cell types and how different cargos influence the range of EV targeting bioactivities,” explained lead author Inna Nikonorova.

Unzipping the C. elegans immune response to viral infection

Unzipping the C. elegans immune response to viral infection

The zip-1 gene in the worm Caenorhabditis elegans has been identified as the central hub for immune response – providing new avenues for research into human immunity against viruses.

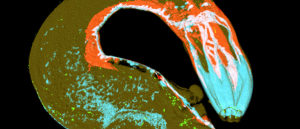

To track the EVs, the research team developed a method using genetically encoded, fluorescently-tagged cargo, followed by proteomic profiling. They tracked cargo produced by nerve cells and focused on EVs produced by cilia, the hair-like structures that extend from cells and transmit and receive intercellular signals. This revealed that EVs carry both RNA-binding proteins and RNA, which indicates that they also play a role in extracellular RNA-based communications.

“Using this strategy, we discovered four novel cilia EV cargo. Combined, these data indicate that C. elegans produces a complex and heterogeneous mixture of EVs from multiple tissues in living animals and suggests that these environmental EVs play diverse roles in animal physiology,” said Nikonorova. The researchers hypothesize that neurons drive communication between cells and between animals by packaging RNA and RNA-binding proteins together in EVs.

As EVs are membrane-bound organelles, they are protected from the environment and could be a promising candidate for targeted drug delivery. The research team is hoping to continue uncovering the mechanisms behind EV-mediated RNA communication, as this understanding could be used to design and synthesize EVs for RNA-based therapies to treat neurodegenerative diseases.