Is your liver as old as your brain?

New research into cell aging surprises scientists by revealing that some organs are a mixture of old and young cells; some of which are even as old as neurons.

Neurons have long been considered one of the oldest cell populations in the body. New research, published in Cell Metabolism, has found that the livers, pancreases and brains of rodents contain cells and proteins as old as some neurons.

Rafael Arrojo e Drigo, staff scientist at the Salk Institute (CA, USA) and first study author, commented: “There is this general idea that neurons are old, while other cells in the body are relatively young and regenerate throughout the organism’s lifetime…We set out to see if it was possible that certain organs also have cells that were as long-lived as neurons in the brain.”

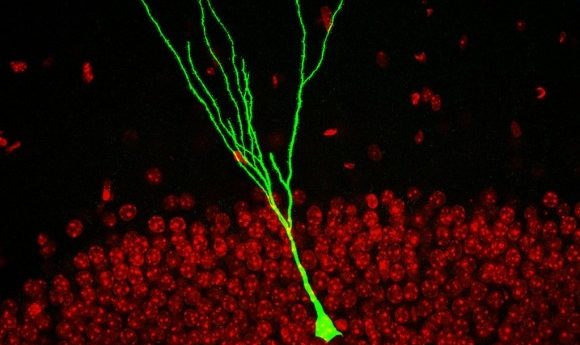

Neurons are largely quiescent cells; they do not actively divide and are not replaced during an individual’s lifetime. Therefore, the team used the age of neurons as an ‘age baseline’ in the study, to contrast the ages of other, non-diving cells against.

“Determining the age of cells and subcellular structures in adult organisms will provide new insights into cell maintenance and repair mechanisms and the impact of cumulative changes during adulthood on health and development of disease.”

Electron isotope labeling and multi-isotope imaging mass spectrometry-electron microscopy (MIMS-EM) were employed to visualize and age cells and proteins in the brains, livers and pancreases of young and old rodents.

Proof of method was provided by first aging neurons from the rodents. As expected, the age of the neurons matched the age of the organisms.

Surprisingly, however, endothelial cells lining the vasculature were found to be of the same age as the neurons, indicating that a subset of non-neuronal cells is not regenerated throughout an organism’s lifespan.

The most striking example of ‘age mosaicism’ – where cells of differing phenotypes (in this case, age) are closely arranged in one tissue or organ — was observed in the islets of Langerhans of the pancreas.

-

Source of new neurons for the hippocampus

-

How does the liver regenerate?

-

Novel drug combination converts glia to restore neuron function

In the islets of Langerhans, some insulin-producing beta cells were found to be relatively young, implying that they consistently replicate throughout an organism’s life. Contrastingly, delta cells were found to be very old as they did not replicate at all.

Similar ‘age mosaicism’ was observed in the livers of rodents. This was particularly unexpected as other studies have demonstrated the ability of the adult liver to regenerate, leading the team to assume that only relatively young cells would be found in this organ.

This concept of ‘age mosaicism’ was found to extend to the molecular level too. Protein complexes within older, non-dividing cells were not uniform in age.

Martin Hetzer, Vice President of the Salk Institute and senior study author, commented that the data: “…suggests even greater cellular complexity than we previously imagined and has intriguing implications for how we think about the aging of organs, such as the brain, heart and pancreas.”

Hetzer added: “Determining the age of cells and subcellular structures in adult organisms will provide new insights into cell maintenance and repair mechanisms and the impact of cumulative changes during adulthood on health and development of disease…The ultimate goal is to utilize these mechanisms to prevent or delay age-related decline of organs with limited cell renewal.”