Saturated fatty acids disrupt the ER

Researchers found that saturated fatty acids interfere with ER lipid dynamics in cells—a strange and previously undocumented phenomenon.

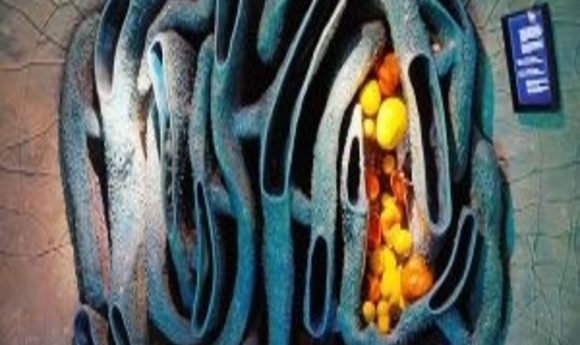

While most people have heard that unsaturated fats—vegetable oils, nut oils, fish oils—are good, and saturated fats—animal fats, butter—are bad, little is known about how cells actually react to different kinds of fats on a molecular level. Now, a research team led by Wei Min at Columbia University reports in PNAS that saturated fatty acids disrupt the lipid membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Specifically, solid lipid domains begin to appear in the usually fluid ER.

“Our study provides a very quantitative description of how cell membranes are susceptible to modulation,” said Yihui Shen, first author of the study. While previous studies had focused on the normal behavior of organelle lipid membranes, none of them documented what happens when external nutrients disrupt this behavior.

When she first joined Min’s group, Shen studied protein metabolism using an imaging technique called Raman spectroscopy to show the distribution of individual molecules. She soon realized that this technique could also be applied for studying fatty acids.

Rather than using traditional Raman spectroscopy through fluorescence imaging, Shen tagged molecules with deuterium. “The unique aspect of our technique is the minimal perturbation of the molecule,” said Shen.

Shen provided the cells with saturated fatty acids in their nutrient source. She was surprised to see that this caused solid saturated lipid domains to cluster in the ER membrane, a finding that had never been described before. Furthermore, adding unsaturated fatty acids reversed this effect.

“When we first saw the phenomenon, we had no clue what it was,” said Shen. “We struggled a bit looking at the underlying biology, but we finally got through the problem.”

Shen’s group postulated that the metabolites of saturated fatty acids end up in the ER, clustering due to their chemical conformation. The straight long chains of saturated fatty acids seemed to pack tightly into solid domains, which could later be disrupted by the bent chains of unsaturated fatty acids. Using Raman spectroscopy, the group confirmed that this behavior does indeed occur in the ER.

“Our study comes into this unique niche because we can see the molecule and how it changes the cell directly by a microscope,” said Shen. Their study is the first to provide this precise spatial and dynamic information on where the metabolites of fatty acids cluster.

“[This study] serves clearly as an important reference, and I think it encourages us to also try Raman spectroscopy,” said Robert Ernst, an investigator at Saarland University in Germany who was not involved with the study.

In the future, Shen would like to further investigate the physiological relevance of these findings. “We found that natural fatty acids caused this membrane change, so the next question naturally is, ‘how does the solid membrane contribute to cell stress?’ Another question is, ‘how is this related to physiology?’ In what condition in the body or in tissues will you observe the solid membrane?” While the team has figured out what happens on a cellular level, they hope to more tightly link their findings to physiology and disease.