Why do some T cells stay in the gut?

Researchers find out what keeps T cells patrolling the gut by decoding their communication with epithelial cells.

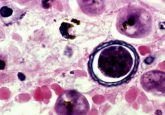

T cells generally circulate around the body until they need to mount an attack; however, some will stay and monitor a specific tissue. One such example is intraepithelial T cells, found around epithelial cells lining the gut. This immune surveillance of the intestinal epithelium is essential to ensure homeostasis in the intestine and protect against infections.

“The T cells move around the epithelial cells as if they are truly patrolling,” described Mitchell Kronenberg (La Jolla Institute for Immunology; CA, USA), senior author of the study, which examined why intraepithelial T cells remain in the gut. “We’ve got some insight on what gets T cells to the gut, but we need to understand what keeps them there.”

Kronenberg’s research group hopes that by finding out why these T cells stay circulating in the gut epithelium, they can begin to understand conditions where there are too many T cells gathered in the intestines, for example in irritable bowel disorder.

New study identifies subset of T cells that regulate the immune system

New study identifies subset of T cells that regulate the immune system

Researchers find that blocking the checkpoint protein PD-L1 unexpectedly activates regulatory T cells (effector Tregs), reducing the ability of the immune system to fight off infections.

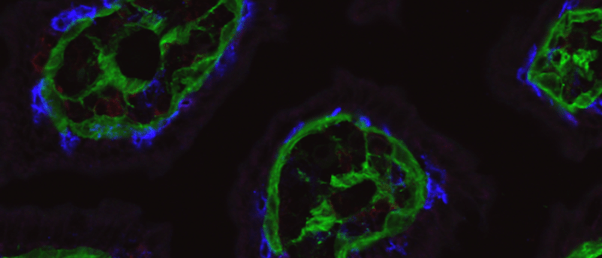

The study revealed that epithelial cells express a protein called herpes virus entry mediator (HVEM), which is known to have a range of functions in augmenting or inhibiting the immune response. By using intra-vital imaging RNA sequencing, the researchers investigated HVEM’s role in the gut. They also found that a thin layer of protein beneath the epithelium, called the basement membrane, was essential for the communication between epithelial cells and T cells.

The experiments showed that without HVEM, the epithelial cells produce less collagen and other structural components that are needed to sustain a healthy basement membrane. Without enough basement membrane, T cell survival worsened.

First, epithelial cells receive a signal through HVEM found on their surface, stimulating the synthesis of the basement membrane protein. The patrolling T cells then detect the basement membrane via integrins, which are adhesion molecules expressed on the surface of a T cell. This interaction between basement membranes and T cell integrins promotes T cell survival and ensures they continue patrolling the epithelium.

Using a knockout mouse model where HVEM was removed from epithelial cells in the gut, the researchers demonstrated that HVEM was essential to gut health and in keeping intraepithelial T cells fit to continue patrolling.

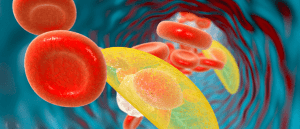

The mice were also infected with Salmonella typhimurium, a bacterium that causes gastroenteritis. The researchers reported that the infection took over the intestines and spread to the liver and spleen, indicating that the T cells were much less effective without HVEM signals from the epithelial cells.

This research suggests that T cells stay in the gut because HVEM indirectly communicates with them through the basement membrane and facilitates their survival in the intestines.

Kronenberg added that there were also signs that a lack of HVEM can change the composition of the gut microbiome, even if there are no pathogenic bacteria present. Next, the research group is interested in finding out what role HVEM plays in maintaining a healthy gut microbiome.