In vivo CRISPR enters the clinic

CRISPR—Cas9 editing has been used in vivo for the first time as part of a treatment to restore sight to those with an inherited form of congenital blindness.

Clinicians working on the BRILLIANCE clinical trial recently announced that the first patient has successfully received an in vivo CRISPR therapy, the first of its kind to be used in the human body. Designed as a treatment for Leber congenital amaurosis 10, and eye disorder of the retina, the CRISPR—Cas9 therapy targets the CEP290 gene and repairs the disease-causing mutations.

The trial, run by Oregon Health & Science University (OSHG; USA) and sponsored by Allergan Plc (Dublin, Ireland) and Editas Medicine (MA, USA), aims to assess the safety, tolerability and efficacy of the treatment and, if found safe in this first patient, will involve 18 other participants.

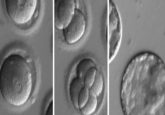

The therapy, known as AGN-151587 (EDIT-101), is delivered to the patient via a subretinal injection into the light-sensing photoreceptor cells of the retina. These cells do not divide, so once edited the changes are permanent.

It could take up to a month before they know whether the treatment was successful; however, positive results in animal models have given the trial runners hope. It is believed that only between one tenth and one third of retinal cells are required to be fixed in order the restore vision – in animal models, scientists were able to correct half.

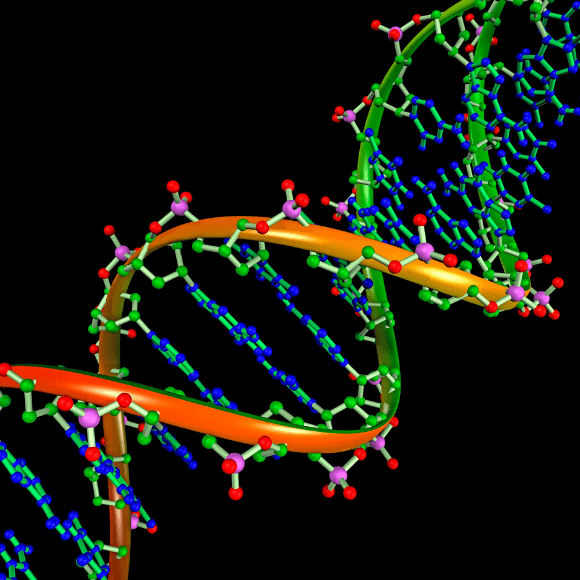

Base editing, a recent iteration of the CRISPR technique, has been demonstrated to cure cystic fibrosis in patient-derived stem cell-based intestinal organoids.

Doctors state that the surgery itself poses little risk, and infections and bleeding are likely rare complications. Off-target effects of CRISPR pose the biggest threat to the treatment, though the researchers did all possible to reduce the risk and ensure that DNA edits were only made where necessary. The treatment stays in the eye and cannot pass to other parts of the body.

There are currently no treatments for Leber congenital amaurosis 10 and those with it are either born blind or lose their sight within the first decade of their life.

“Being able to edit genes inside the human body is incredibly profound,” commented trial leader Mark Pennesi (OSHU). “Beyond potentially offering treatment for a previously untreatable form of blindness, in vivo gene editing could also enable treatments for a much wider range of diseases.”

This in vivo approach marks a turning point for CRISPR-based therapeutics, as previous gene-editing techniques have involved editing the genetic material once it has been removed from the body. Unlike the vigilante approach taken by the infamous ‘CRISPR babies’ gene-editing research group, this trial has the approval of government regulators and follows gene-editing guidelines; any edits made will not be passed to future generations.

Back to basics with CRISPR

Back to basics with CRISPR