Detecting SARS-CoV-2: how does COVID-19 testing work?

Having participated in a recent COVID-19 testing study, Abigail Sawyer describes the testing process and answers frequently asked questions about COVID-19 testing.

I love science. Particularly the scientific method; asking questions, theorizing and experimenting to find the answers. So, whenever I am asked to be involved in anything even remotely concerning science, I jump at the chance. This has led to me being involved in some questionable ‘science experiments’ for TV, but most recently, an Imperial College London (UK) study with the aim to improve COVID-19 testing.

I never receive mail – partly because I think this physical form of contact is (sadly) dying out, and partly because I opt to receive most communications via email to cut down on waste. Still, receiving mail is one of my favorite things – and any mail I do receive tends to be all the more special.

So, when I heard my letterbox on a normal working from home day, I jumped up from my desk chair and ran downstairs to see what had been delivered. The envelope didn’t give much away, but when I opened it, I realized that it was inviting me to participate in a study that I had been randomly selected for. I couldn’t believe my luck!

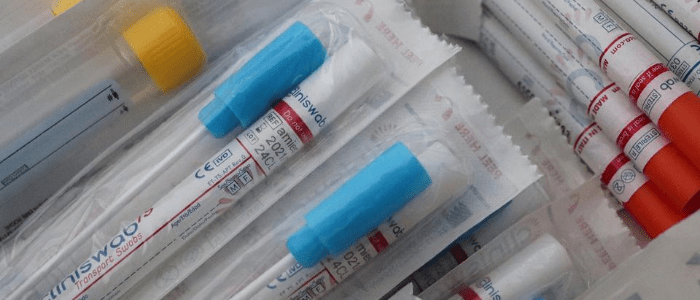

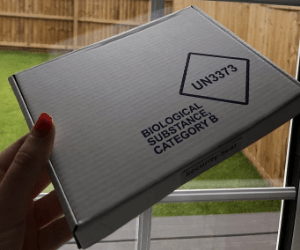

After signing up online, I booked a day in for my samples to be collected via courier and then waited for the kit to be delivered. The kit arrived with a 15-page instruction booklet – somewhat overwhelming – and the means to collect both nasopharyngeal swab and saliva samples.

What COVID-19 tests are available?

Currently, there are two different types of COVID-19 test – the viral test that can detect the presence of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) and an antibody test that can potentially detect the presence of three different types of SARS-CoV-2 specific antibodies (Immunoglobins A, G and M) in the blood.

Generally, the antibody tests require a blood sample that is collected by a healthcare professional and can tell you if you’ve been infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the past. Primarily, the viral tests involve PCR on a sample collected by a nasal swab to detect if a person is currently infected with SARS-CoV-2.

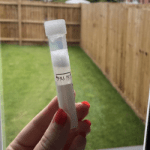

On the day of the sample collection, I woke up and got on with my sample collection straight away. First up was the saliva test. Aside from no eating or drinking for 30 mins beforehand – usually a challenge for me – this was incredibly straightforward. It was self-explanatory; I collected my saliva in a tube and mixed in some liquid that was also provided.

On the day of the sample collection, I woke up and got on with my sample collection straight away. First up was the saliva test. Aside from no eating or drinking for 30 mins beforehand – usually a challenge for me – this was incredibly straightforward. It was self-explanatory; I collected my saliva in a tube and mixed in some liquid that was also provided.

What is the COVID-19 saliva test?

The COVID-19 saliva test is an alternative method of sample collection for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection that is currently being explored and trialed. It relies on PCR to detect SARS-CoV-2 but is an easier, less invasive and cheaper method of sample collection than the nasal swab. Early results also indicate that it is just as accurate as the nasal swab, however, it needs to be more widely tested before it can replace the nasal swab as the primary avenue of sample collection for COVID-19 diagnostics.

Next up was the nasopharyngeal swab, which involved swabbing both the back of my throat and my nasal passage. This was definitely uncomfortable, though not unbearable, and there was an obvious difference in the length of time and complexity of this method of sample collection in comparison to the saliva.

Next up was the nasopharyngeal swab, which involved swabbing both the back of my throat and my nasal passage. This was definitely uncomfortable, though not unbearable, and there was an obvious difference in the length of time and complexity of this method of sample collection in comparison to the saliva.

In the instructions, there was a huge emphasis on preventing cross-contamination with multiple steps to clean surfaces and wash hands, not so tough when you’ve done years of lab work, but perhaps an easy  mistake to make for the general population.

mistake to make for the general population.

The samples then had to be placed in labeled biohazard bags, packaged up and put in the refrigerator to slow any potential degradation of the samples while waiting for the courier to collect them.

What is the COVID-19 swab test?

The nasopharyngeal swab was the first widely used method of sample collection for COVID-19 viral testing. It involves the use of a Q-tip style cotton swab to sweep across the tonsils and the back of the throat before inserting into a nostril until some resistance is felt and swabbing there. Some countries have now progressed onto just a nasal swab, without the need to sweep the throat additionally.

The negatives of using the swab for COVID-19 testing are that children and some vulnerable adults may require help with administering the swab or may not be able to use it at all. It is invasive, uncomfortable and a more expensive and complex process than the use of saliva.

A few days later, I received my results, which were negative. This means at the time I took my samples; it is highly unlikely that I had COVID-19. These results were not a surprise to me as I had no COVID-19 symptoms, however, it would’ve still been possible that I was asymptomatically infected with SARS-CoV-2.

PCR may be the current gold-standard of SARS-CoV-2 detection, but will it stand the test of time? There are already smaller, point-of-care detection methods being trialed, including the DETECTR CRISPR platform and LamPORE – using RT-LAMP. In order to provide cheaper, faster and less-invasive testing, accuracy often has to be the trade-off. Will more efficient testing triumph over accuracy, or will the diagnostics community provide a test that can win overall?

When should you take a COVID-19 viral test?

If you suspect you have COVID-19 or have been in close contact with someone who has had a positive COVID-19 test result, whether or not you have any symptoms, you should seek to take a viral test by contacting your healthcare provider.

A positive test means you should isolate for 10 days (according to the CDC). However, even if you have a negative test, you should continue to practice social distancing and following preventative measures.

When should you take a COVID-19 antibody test?

The antibody test might be able to tell you if you have had COVID-19 in the past, but currently these are only being routinely offered to healthcare professionals or hospital inpatients, based on the advice of their clinician. Decisions on whether to offer a COVID-19 antibody test lie with local healthcare providers.

The antibody tests cannot tell you the level of antibodies or subsequent level of immunity from COVID-19.

Are COVID-19 tests accurate?

Studies have suggested that as many as 30% of PCR tests for COVID-19 are inaccurate. False-negative results are much more common than false-positive results as the viral RNA needs to be detected in order to produce a positive result, however, this does not necessarily mean you are still infectious – PCR tests can remain positive for several weeks after an active infection.

False negatives can occur if a good sample is not collected – this can happen both with at-home sample collection and with collection by a healthcare professional. You can also produce a false negative result if there is not a sufficient incubation period for the virus (you are tested too soon after exposure) or if you have waited too long after exposure to be tested.

Which COVID-19 test is the most accurate?

Despite the potential high percentage of COVID-19 tests deemed to be inaccurate, PCR tests are still the most accurate form of COVID-19 testing if performed correctly.

Are COVID-19 antibody tests accurate and reliable?

Just as COVID-19 viral tests can produce false negatives, so can COVID-19 antibody tests. It takes time after infection to build a supply of antibodies, so levels in the blood may not be high enough to detect and some people never produce antibodies.

False positives can also occur as some SARS-CoV-2 antibodies are similar to those that are produced from infection with another member of the coronavirus family.

At the present time, antibody test results are useful for scientists to use for studies and predictions. However, not very much is known about the level of immunity provided by COVID-19 antibodies, so the same precautions should be followed.

At-home blood sample collection by a finger prick is currently being trialed but, at present, the results are not accurate enough to be rolled out as an approved testing method.