Bacteriophage ‘Muddy’ buddies up with antibiotic to combat antibiotic resistance

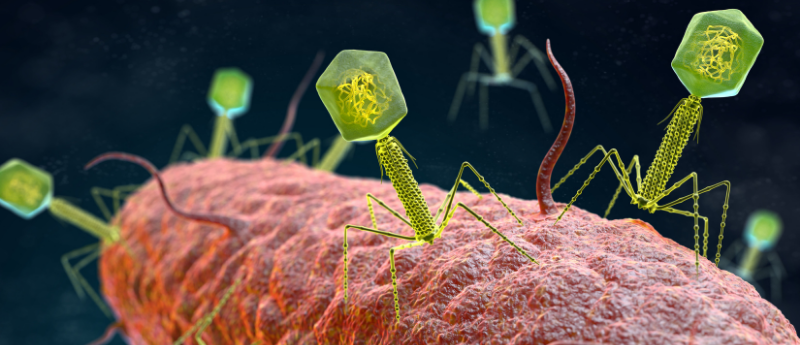

Researchers discover bacteriophage, named ‘Muddy’, and antibiotic rifabutin as a new dynamic duo combination therapy against antibiotic-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus infection in a cystic fibrosis zebrafish model.

A group of researchers from Universite de Montpellier (France) and University of Pittsburgh (PA, USA) have discovered a new combination therapy against an antibiotic-resistant strain of M. abscessus. Led by Matt D. Johansen (Université de Montpellier), the study assessed the survival rates of zebrafish with cystic fibrosis when infected with an antibiotic-resistant strain of M. abscessus and found that the bacteriophage–antibiotic duo improved survival rate far better than when either treatment was used alone. The study demonstrates that zebrafish are a valuable model for studying bacteriophage–bacteria relationships and that this combination therapy could eventually be used for patients in the clinic.

The bacteria in question, M. abscessus, similar to closely related strains Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium leprae, often infects the lungs of its host. In humans this infection can be severe and is often exacerbated due to antibiotic-resistance. As such, multidrug resistant M. abscessus is notoriously difficult to clear in cystic fibrosis patients due to their suppressed lung capacity and function; therefore, clinicians are left with few therapeutic options.

Researchers are beginning to study bacteriophages as potential key players in fighting drug-resistant infections. However, these studies are too risky to conduct in human patients. “We need clinical trials, but there will be many other questions to be answered on our way there […] and zebrafish provide a very helpful tool for advancing these questions,” co-author Graham Hatfull (University of Pittsburgh) explained.

The tortoise and the antibiotic: a tale of environmental pollution

The tortoise and the antibiotic: a tale of environmental pollution

The giant Galápagos tortoises inhabiting the most human-populated island of the archipelago have acquired more antimicrobial resistant genes (ARGs) than those that live in more isolated ecosystems with little human contact.

To create a cystic fibrosis animal model, the researchers injected zebrafish embryos with morpholinos, a type of oligomer molecule used in molecular biology, which specifically targeted the zebrafish cftr gene to suppress its expression. This gene knockdown procedure allowed the team to induce the same genetic mutation that causes cystic fibrosis in humans in the zebrafish model, causing the zebrafish to develop cystic fibrosis and be more susceptible to severe M. abscessus infection.

The cystic fibrosis zebrafish embryos were then infected with M. abscessus and monitored for 12 days. The zebrafish developed serious infections and abscesses, leading to only 20% survival rate. The team then tested how well the Muddy bacteriophage and the rifabutin antibiotic could independently improve the survival rate of infected zebrafish. They found that over the course of 5 days with either Muddy or rifabutin treatment, the severity of infection decreased, the fish had fewer abscesses and showed an improved survival rate of 40% in both cases. Remarkably, when administering the infected fish with both Muddy and rifabutin in combination for 5 days, the condition of the zebrafish improved significantly, and survival rate increased dramatically to 70%.

The success of the combination therapy in the zebrafish model is promising and the team remain optimistic that, with continued research, the therapy will eventually be available to cystic fibrosis patients in the clinic. Until then, lead author Matt Johansen is confident that animal models will help pave the way to finding successful disease treatments, concluding: “we believe that zebrafish will help us understand many bacteriophage–bacteria pairings in our fight against multi-drug resistant pathogens.”