Does anemone venom have the power to beat chronic pain?

Researchers have found that sea anemones produce specific venoms in different regions depending on their intended function, creating a path to more straightforward drug design.

When used carefully, we can design therapeutic drugs based upon the chemical makeup of toxins in venoms. Scientists from Queensland University of Technology (Brisbane, Australia), led by Lauren Ashwood, have identified functionally specific venom from an anemone that could prove fruitful for the development of therapeutics for pain relief or digestive issues.

Snake venom is commonly studied, analyzed and used for therapeutic design. However, snake venoms cause a plethora of different reactions, and each venom has a unique cocktail of toxins – sometimes containing hundreds of compounds – stimulating different biological mechanisms. This cocktail presents a challenge for scientists trying to identify the specific compounds for responsible for different reactions – the hunt for potential therapies is like a stab in the dark.

Jellyfish collagen: zapping mammalian-source cell cultures into the past?

Jellyfish collagen: zapping mammalian-source cell cultures into the past?

A study demonstrates jellyfish collagen to be a reliable and sustainable alternative to current mammalian sources for use in cancer cell culture.

Researchers hope that studying venoms and toxins in the context of their functionality will help define appropriate therapeutic uses for the toxins discovered. So, when Ashwood discovered that the anemone Telmatactis stephensoni produced different venoms specific to different functions, she decided to explore the organisms venoms in greater depth.

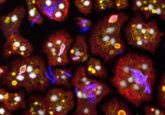

Telmatactis stephensoni produces toxins in stinging cells in three major functional regions – the tentacles, epidermis and gastrodermis. Using transcriptomic and proteomic approaches the team analyzed the venoms produced at each of these regions. This allowed the group to make contextual assumptions on the function of the toxin based on the area it is produced. The team inferred that the toxins produced by cells in the tentacles are designed to cause pain and defend, while the toxins released in the gastrodermis are intended to assist with digestion.

With the likely function of toxins found in each venom significantly narrowed down, the team are now in a much better position to investigate their therapeutic potential in a toxin-driven approach.

“In all, we found 84 potential toxins in T.stephensoni, including one that hadn’t been seen before.” Explained Lauren. “A sample of this unknown toxin, named U-Tstx-1, has been sent to a specialized lab in Hungary for analysis.” Researchers know this toxin was produced in the gastrodermis of the anemone and means assumptions can be made about its function. “It could be involved in digestion – it could be a new type of co-lipase, enzymes that break down fat. This toxin could also be similar to a toxin in the venom of black mamba snakes that stimulates intestinal muscle contractions.”

The region of particular interest to co-author Peter Prentis is the acontia, which is similar to a jellyfish tentacle and causes extreme pain. “If we can isolate the neurotoxin and find the nerve cell receptor it activates, we could potentially develop a blocker to stop activation and treat conditions such as chronic back pain.”

There is hope that further investigation into the toxins discovered by the team at the Queensland University of Technology will lead to the powerful therapeutic drugs of the future.