Novel multi-organ-on-a-chip system could revolutionize drug development

Researchers have developed a novel multi-organ-on-a-chip that can demonstrate toxicity more accurately than standard methods.

Current drug testing practices have resulted in a large number of drugs being approved for widespread human use, only to be recalled later on as a result of unanticipated toxicity. Drug development is an expensive process as it is, and the costs, both financial and in human lives, rise considerably if that drug is later withdrawn.

Now, in an effort to improve toxicity screenings in drug trials and prevent this from occurring, a research team from the Wake Forest School of Medicine (NC, USA) has developed a novel multi-organ-on-a-chip that is able to test how a drug will affect vital organs in the human body.

Interested in this piece? Click here to check out the rest of our spotlight on 3D cell culture.

“The cost for bringing a single drug to market, with all direct and indirect expenses accounted for, can climb as high as $2.6 billion,” commented Anthony Atala, the study’s senior author. “As both adverse human effects and drug development costs increase, access to more reliable and affordable drug screening tools is increasingly critical.”

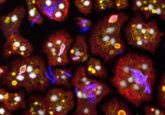

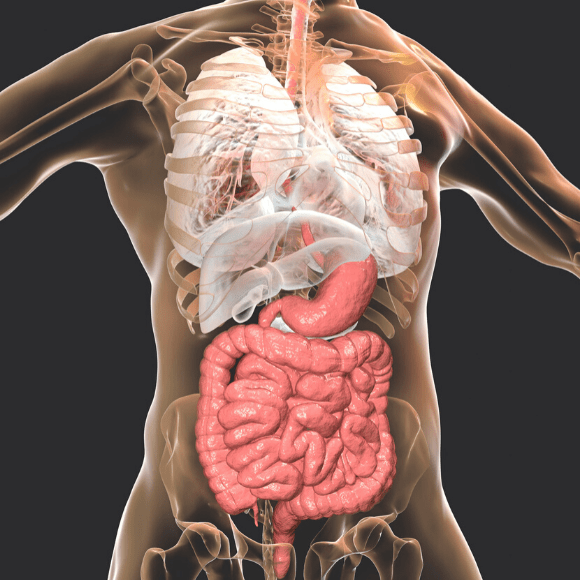

Described in a recent study published in Biofabrication, the integrated system contained six different tissue types – liver, heart, vasculature, lungs, testis and either colon or brain tissues – and a common circulating media. Combining the organoids allowed the researchers to observe more complex responses, such as how the response of one tissue type impacted another.

A modern-day Frankenstein’s monster?

A modern-day Frankenstein’s monster?

Lab-grown model of the human body comprised of an integrated body-on-a-chip multi-organoid system could pave the way for quicker pharmaceutical testing.

The multi-organ-on-a-chip system was utilized to screen for toxicity in pergolide, rofecoxib, valdecoxib, bromfenac, tienilic acid and troglitazone; six drugs that had all previously been withdrawn from market by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA; MD, USA) for their toxic effects in humans. For most of these drugs, the 3D organoid system was able to demonstrate toxicity.

“These compounds were tested by the pharmaceutical industry and toxicity was not noted using standard 2D cell culture systems, rodent models, or during human Phase I, II and III clinical trials. However, after the drugs were released to market and administered to larger numbers of patients, toxicity was noted, leading the FDA to withdraw regulatory approval,” Atala remarked. “In almost all these compounds, the 3D organoid system was able to readily demonstrate toxicity at a human-relevant dose.”

Furthermore, by exposing the system to commonly-used drugs that are still available on the market, including aspirin, ibuprofen, ascorbic acid, loratadine and quercetin, the researchers were able to demonstrate that the multi-organ-on-a-chip remains viable when exposed to non-toxic compounds at clinically relevant doses.

“Further study will be needed. But based on these results our system, and others like it, using 3D human-based tissue models with nuanced and complex response capabilities, has a great potential for influencing how in vitro drug and toxicology screening and disease modeling will be performed in the near future,” co-author Aleksander Skardal concluded.