DNA: Do Not Abbreviate?

Is the rising use of scientific acronyms hindering research clarity?

Some widely accepted trends in scientific publishing include that the number of papers is growing year-on-year, papers are becoming increasingly complex and more multidisciplinary, and there is increasing interest in reading research from those outside the field – be that those in different scientific fields or the public. Given the latter, the clarity of a manuscript is important, and scientific acronyms have been highlighted as something that should be reduced to aid the understanding of research papers. Now, a study has delved into the current state of acronyms in scientific research.

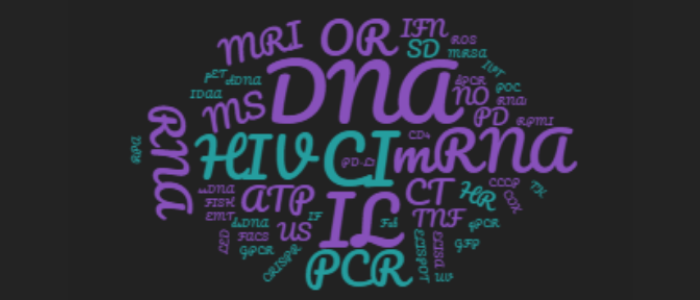

Over 24.8 million titles and 18.2 million abstracts published between 1950 and 2019 were analyzed, yielding over 1.1 million unique scientific acronyms – defined as a word in which at least half of the characters are upper case letters.

The proportion of acronyms in titles rose from 0.7 to 2.4 per 100 words between 1950 and 2019, and in abstracts it rose from 0.4 to 4.1; 19% of titles contained at least one acronym, and 73% of abstracts. Three letter acronyms (ironically shortened to TLAs) were most popular. This increase was seen regardless of article type and remained even when the 100 most popular acronyms were removed.

Ignorance is bliss: workplace gender bias is thriving thanks to those denying its existence

Ignorance is bliss: workplace gender bias is thriving thanks to those denying its existence

To those who have never experienced it, workplace gender bias may seem dead. However, new research suggests it is the people who deny its existence that are keeping it alive.

This use of scientific acronyms risks confusion: “For example, the acronym UA has 18 different meanings in medicine, and six of the 20 most widely used acronyms have multiple common meanings in health and medical literature,” noted co-author Zoe Doubleday (University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia). “When I look at the top 20 scientific acronyms of all time, it shocks me that I recognize only about half. We have a real problem here.”

Other examples of popular acronyms with multiple possible meanings include CI, US and HR.

While some scientific acronyms were used regularly, 79% appeared fewer than 10 times, with 30% being used only once.

While calls have been made for a sparing use of acronyms, this research suggests they do not appear to be having an effect. The authors go on to make some recommendations, noting authors should “avoid using acronyms that might save a small amount of ink but do not save any syllables, such as writing HR instead of heart rate.”

However, they note that making a general rule is difficult and speculate on whether journals in the future should offer two versions of a paper – one with acronyms and one without.

“Our work shows that new acronyms are too common, and common acronyms are too rare,” the authors conclude. “Reducing acronyms should boost understanding and reduce the gap between the information we produce and the knowledge that we use‚ without ‘dumbing down’ the science. We suggest a second use for DNA: do not abbreviate.”