It takes too long to publish

In 2016, publishing on biology preprint servers took off, but many life scientists still hesitate to use them.

It takes months, even years, to publish these days (1), but one solution has attracted some recent attention from biologists. Preprint servers like PeerJ and BioRxiv bypass the traditional peer review process. Instead, researchers simply deposit their manuscripts electronically for the wider world to see, in theory, allowing an audience of experts to comment and contribute valuable feedback.

Synthetic biologist Jessica Polka posted her first paper on a preprint server as a postdoctoral researcher in 2014. “I lost nothing whatsoever by doing it, and for subsequent preprints, I would say I’ve gained tremendous amounts of feedback,” Polka said. She now directs Accelerating Science and Publication in Biology (ASAPbio), an organization in Cambridge, Massachusetts that works to promote the use of preprint servers.

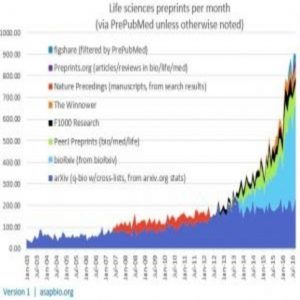

Preprinting is already common practice in physics, math, and computer science. arXiv.org, for example, has been operating since 1991. According to Polka, the rate of preprint posting in biology recently exploded, with 900 new preprint manuscripts currently being posted per month across the preprint servers.

Admittedly, those numbers represent a small fraction of articles available in PubMed. A minority of biologists know about preprint servers, and their use is not emphasized in PhD or postdoctoral training. “They may have heard the term but haven’t fully used [preprints] or [don’t] know what they are,” Polka said. As far as promoting a better understanding, “I think there’s a long way to go.”

Like Polka, those who’ve posted preprint papers report an overwhelmingly positive experience. In fact, the most common complaint from users is a lack of comments or feedback, Polka said.

In Polka’s view, preprint papers and traditional publishing are complementary. “As long as the standards of scientific content and ethics are met, I think preprints could be wonderful way of distributing types of findings that otherwise don’t have a home,” Polka said. These include, for example, negative findings.

However, there is some debate about whether preprint servers contribute meaningfully to science and scientific publishing. In a June 2016 blog post, Cell Press CEO Emilie Marcus wrote, “I always worry about advocates who fail to acknowledge risks or downsides and to discuss them openly and thoughtfully. That’s what turns critical thinking into politics or propaganda.”

The single biggest fear among researchers just learning about preprint servers is that of getting scooped. But this fear hasn’t stopped researchers from presenting their newest work at conferences, preprint supporters say (2).

Another concern is limited time for would-be reviewers, which affects quality. Tricia Serio, professor of molecular and cellular biology at the University of Arizona, recently wrote about erosion in the peer review system. Scientists are overloaded with papers as it is, and preprint servers may only exacerbate this problem.

“I do think that preprints will get reviewed by the community in that space, but I think it might take a lot longer to really vet,” Serio said. “The volume will be so huge that it will be impossible for people to keep up.” Indeed, Cell Press’s informal survey reports that only 6% of respondents had commented on another researcher’s preprint article; the main reason they cited for this was a lack of time.

Automated alerts for articles, RSS feeds, and better search tools such as PrePubMed and OSF Preprints, an aggregation server created by the Charlottesville, Virginia-based nonprofit Center for Open Science, will help with information overload.

ASAPbio is also currently conducting discussions with an international group of funders for the creation of a new aggregation service. “The idea is that we’re not just collecting the metadata (article title, authors) but we’re also collecting the full text of those preprints with permissive licensing,” Polka said. She agreed that better ways of digesting new information are needed.

Once researchers are better able to find applicable preprint papers, reviews and comments should increase, improving the quality of those manuscripts. Jordan Anaya, creator of PrePubMed, believes that reputation should motivate scientists to share their best work, regardless of the platform. “The people who post preprints want their work to be seen and shared. If you want your work to be seen, that means you’re happy with the work you’ve done,” he said.