Could new gut insight help understand graft-versus-host disease?

New research suggests a mechanism – and potential pharmacological treatment – for microbiome changes that affect the severity of graft-versus-host disease.

A new paper has found that an increase in oxygen levels could cause the dysbiosis observed in severe immune-mediated intestinal conditions. Researchers believe that understanding this mechanism could lead to pharmacological treatments for conditions including graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

GVHD is a potentially life-threatening complication of bone marrow transplants in which allogeneic T-cells attack the recipient’s tissues. This risk limits the number of transplants that occur and means that transplant recipients require immune-suppressing drugs, which increase the risk of infection.

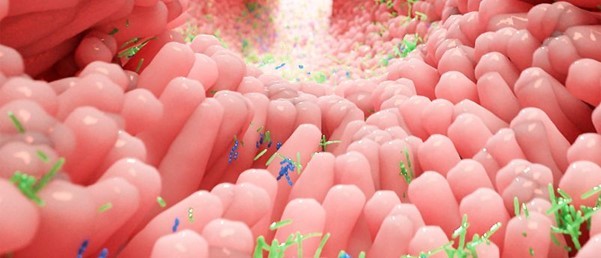

Previous research identified that changes in gut bacteria are associated with the severity of GVHD, but the cause of this was unknown. In the current study, researchers at Baylor College of Medicine (TX, USA), University of Michigan (MI, USA) and collaborating institutes, found that damaged intestinal epithelial cells release oxygen into the lumen, creating a more aerobic environment. This causes dysbiosis as most of the ‘good’ intestinal bacteria are anaerobic, so increased oxygen levels are toxic to them.

Characterizing metabolite messengers: how the gut and brain communicates

Characterizing metabolite messengers: how the gut and brain communicates

A recent study investigated metabolites using a novel tool to find out how the gut and brain communicate.

Senior author Pavan Reddy (Baylor College of Medicine) explained, “An increase in oxygen level provides an explanation for the microbiome changes in the context of these inflammatory diseases.” The team suggested that returning the gut to anaerobic conditions might reverse the imbalance in gut bacteria and reduce disease severity.

The researchers tested this hypothesis in animal models of GVHD. The team identified that iron chelators – an existing class of drug that is clinically well understood – can reduce the levels of oxygen in the gut. Reddy said, “In our animal models, iron chelators removed iron from the intestine and that facilitated the restoration of an oxygen-poor environment that gave anaerobic bacteria an opportunity to bloom. Importantly, this reduced the severity of GVHD.”

The researchers now hope to conduct further studies to assess whether iron chelation can help control GVHD in patients who have had a bone marrow transplant.