Novel human T Cells might have cancer-fighting potential

Researchers uncover a new type of T cell that recognizes self-antigens and could one day be used for tumor immunotherapy.

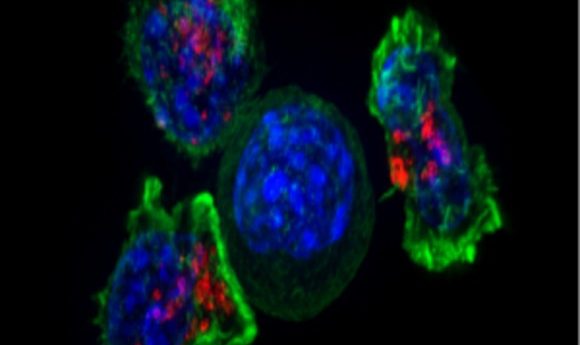

Superresolution image of T cells surrounding a cancer cell (center).

Credit: Wikimedia

A newly discovered T cell population could play wide-ranging roles in human immunity and has the potential to be harnessed for cancer treatment, according to a recent study. As reported in eLife, researchers found that these so-called MR1T cells recognize self-antigens presented by a protein called MR1, which was previously only known to play a role in presenting microbial antigens to a different T cell lineage.

“To date, there was no information on the ability of the MR1 molecule to present endogenous antigens expressed by mammalian cells, and in particular those associated with cancer cells,” said study co-author Lucia Mori from the University of Basel. “We have isolated and characterized a novel T cell population that recognizes MR1-positive tumor cells. These MR1T cells recognize and kill many human tumors derived from different tissues.”

T cells detect a broad range of microbial antigens and self-antigens and help protect against pathogens and cancer. For example, mucosal associated invariant T (MAIT) cells, which recognize microbial metabolites presented by MR1, mediate direct killing of infected cells. But until now, it was unclear whether the role of MR1 extended beyond presenting microbial metabolites to MAIT cells.

In the new study, Mori and her colleagues discovered that MR1 presents self-antigens to human MR1T cells, which respond to MR1 in the absence of microbial antigens and are readily detectable in blood from healthy individuals. MR1T cells exhibited T-cell receptors (TCRs) with diverse antigen specificities, expressed a broad range of cytokines and chemokine receptors, and secreted diverse molecules following antigen stimulation. These findings suggest that MR1T cells may have wide-ranging roles in various sites throughout the body.

Consistent with this notion, the researchers found that MR1T cells induced the maturation of antigen-presenting cells called dendritic cells. MR1T cells also promoted innate defense in intestinal epithelial cells, which form a single protective layer that prevents harmful microorganisms in the gut from reaching circulation. Moreover, some activated MR1T cell clones displayed unusual functions, including the release of growth factors that support the formation of new blood vessels, suggesting a potential role in tissue remodeling processes.

Additional studies are needed to uncover the roles of MR1T cells in human diseases such as cancer. From a clinical standpoint, one important feature of MR1 molecules is that they are the same in all individuals, so the same MR1T cell can recognize cancer cells from different patients, Mori explained. “The transfer of TCR genes into recipient T cells confers recognition of tumor cells, implicating the transfer of MR1T-TCR genes to patients’ T cells as a novel approach to tumor immunotherapy,” she said. “This new type of tumor cell recognition and killing could have widespread implications for the whole human population and the immediate future of cancer treatment.”

According to Mori, the next challenge is to identify the tumor-associated antigens that induce MR1T cell activation and the killing of cancer cells. “These studies will pave the way for new and broader strategies to combat human tumors.”