Bringing antigen retrieval to you in an instant…pot?

Researchers have demonstrated the use of an everyday kitchen appliance as a simple, affordable and accessible alternative for performing heat-mediated antigen retrieval.

Researchers from the University of Rochester Medical Center School of Medicine and Dentistry (NY, USA) have found an enterprising hack for immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies. In a recently published study, the team detailed a simplified method for antigen retrieval using a common household appliance: the Instant Pot. By completing a successful proof of concept study with this multipurpose cooking device that can pressure cook, air fry, roast, bake, dehydrate and slow cook, this technique could spare the budgets of many labs around the world.

For many diseases, IHC is the gold standard for clinical diagnosis, using antibodies to selectively identify antigens in tissue sections. A key step for antigen detection is antigen retrieval, however, the high cost of traditional equipment hinders IHCs’ use in labs with limited budgets. In response, Nolan Kearns, the lead author on the study, and co-authors, set out to develop an affordable and accessible method for performing heat-induced antigen retrieval. In the end, they had to look no further than their kitchen counter for the solution.

Near-infrared spectroscopy detects food allergens

Near-infrared spectroscopy detects food allergens

Researchers demonstrate that near-infrared spectroscopy is a reliable and fast method to detect contaminants in food products, and can detect multiple contaminants simultaneously.

Coplin jars filled with buffer were pre-heated inside the mini Instant Pot. Sample slides were then added, and heat retrieval performed. To validate the method, the researchers tested sections of transplantable Colon 38 (C38) tumor cell line grown in syngeneic C57BL/6 mice, known to contain an abundance of CD8 cells, for an anti-CD8 antibody. Sections of C38 cell line that had been processed with the Instant Pot antigen retrieval method were subsequently stained with anti-CD8 antibodies and compared against sections that received no antigen retrieval treatment as a control.

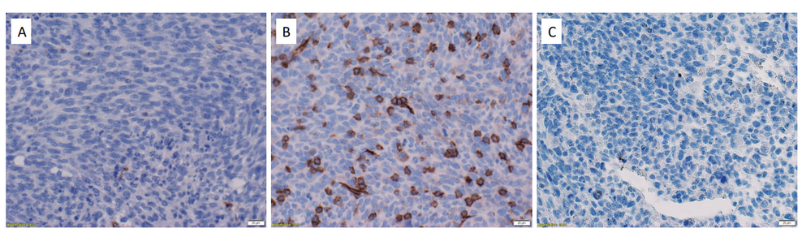

The results reflected the effectiveness of the method. Sections that underwent the Instant Pot method showed strong positive staining of CD8 cells, whilst samples that received no antigen retrieval treatment showed only slight staining (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Successful staining of CD8 cells in Colon 38 tumour tissues. (A) C38 tissue section that did not receive antigen retrieval was stained with a rabbit antimouse mAb to CD8α, a cell surface marker expressed on cytotoxic T cells. (B) C38 tissue that received antigen retrieval was stained with an antimouse mAb to CD8α. (C) C38 tissue that received antigen retrieval was stained with a rabbit IgG isotype control mAb.

Using normal tissue and tumor samples, the team trialed the method’s applicability for several different monoclonal antibodies, including ones directed against both cell surface and intracellular antigens. They found that it worked with cell surface antigens including CD4, CD8, NCR1, CD38, and CD31, and intracellular antigens like transcription factors EGR-2 and FoxP3. Tested antibodies gave expected staining patterns, qualitatively similar to what has been reported with other antigen retrieval methods.

The specificity of the staining was assessed using spleen sections stained with an isotype control or with anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 rabbit monoclonal antibodies. The staining was specific; the control showed little staining, whilst the antibodies gave an expected distribution pattern for T-cell populations in the spleen.

Kearns and his team believe that their results and the Instant Pot’s ability to modify its temperature, demonstrate that this method could be applicable to any antibody validated for use with heat-induced epitope retrieval. Future studies could focus on investigating this claim and assessing its suitability for other antibodies. Overall, this method offers a cost-effective, accessible, and user-friendly alternative for antigen retrieval that could make it an attractive option for many labs.