Horror movies effect on the brain: when movies control us

Hitchcock and Kubrick grip us in scenes and sounds of horror. What is the horror movies effect on the brain?

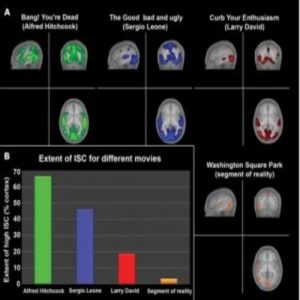

Different genres evoke different reactions in the brain (2).

On October 31st, those with a penchant for all things eerie will engage in Halloween activities such as carving jack-o-lanterns or trick-or-treating. But what fright night would be complete without a movie marathon that leaves you clutching your seat?

Horror films are renowned for captivating audiences’ attention, but how does our brain process these thrillers? Professor of psychology and neuroscience Uri Hasson from Princeton University founded the field of “neurocinematics” in 2004 when he used pioneering neuroimaging techniques to investigate how some movie genres such as horror and action keep us gripped from lights down to credits rolling.

“Many neuroimaging studies involve controlled experiments, with few variables,” said Hasson. “With this, you lose the complexity that comes with the everyday situations you are trying to study. Film provides a balance as a director can control variables through choosing what you see, feel, and think, but they also have complex story arcs and themes for your brain to interpret.”

For Hasson’s initial study published in Science (1), his team performed functional MRI (fMRI) scans on volunteers while they watched the classic spaghetti Western The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly. They analysed their data using the inter-subject correlation (ISC) method, where brain activity from participants enables modeling of other participants’ brain activity. “One way to think about it is that I’m measuring if your brain responses are similar to mine within a particular context,” explained Hasson.

Surprisingly, despite the uncontrolled free viewing of the task and complex narrative, activity was similar across all viewers’ brains. This included regions associated with emotion such as the amygdala, visual areas in the occipital and temporal lobes, and auditory regions in Heschl’s gyrus. Activity across all participants increased and decreased following a similar time course as the plot unravelled.

To insure that this significant correlation was due to the film structure, the team next measured ISC in the dark, using only short segments of the film, and again noticed correlated brain activity between participants. For comparison, they next created a short unedited ten-minute film of Washington Square Park in New York City showing the richness and complexity of life, but containing no plot. ISC was considerably smaller when viewing the unstructured segment of reality.

In 2008, Hasson furthered his research by performing identical fMRI scans with different entertainment genres. Participants watched Alfred Hitchcock Presents (Horror/Thriller), The Good, the Bad, and The Ugly (Western), and Curb Your Enthusiasm(Comedy). The Hitchcock episode significantly evoked the highest amount of ISC similarity, with 65% correlation across all participants. “These results could provide neuroscientific confirmation of Hitchcock’s infamous ability to master and manipulate viewers’ minds,” said Hasson.

According to Hasson, it is important to distinguish between the level of processing devoted to analyzing incoming stimuli and a movie’s effect on viewers. Brain activity variation across viewers (low ISC) could be caused by a less engaged processing of information such as from a wandering mind or from a highly engaged audience who respond in a variety of ways when processing a movie sequence. With further study, the team found that a low ISC does not indicate a lack of interest in a particular film. Curb Your Enthusiasm had the lowest ISC score (18%), but viewers still reported that they were quite engaged.

While Hasson hoped that these findings would become a toolkit for budding movie makers when developing their films, there has been little interest so far. “However, the methodologies developed have come in useful for recent research that has helped us understand how we communicate with each other,” Hasson stated.

Even so, it’s interesting to remember that when you’re watching a gripping thriller, your buddy next to you is experiencing the same brain waves.