What makes us conscious?

What is consciousness and where does consciousness come from? Consciousness—awareness of ourselves and our surroundings—has boggled the minds of neuroscientists and philosophers alike. Now, a new study pinpoints the brain network involved in this intriguing phenomenon.

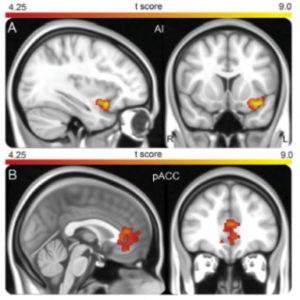

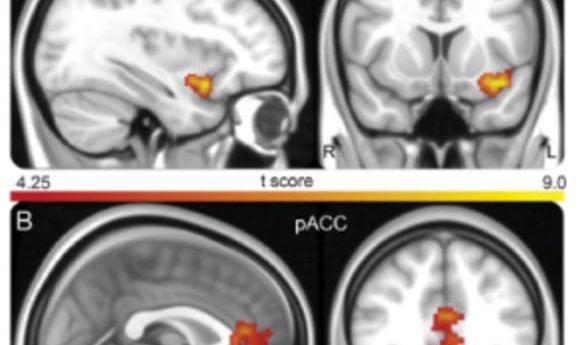

The brain network that supports consciousness (1).

Consciousness—our awareness of our ourselves and our environment, as well as our responsiveness to the latter—remains one of the biggest mysteries of modern science. Researchers have tried to dissect its mechanisms, with limited success. Now, Michael Fox, Director of the Laboratory for Brain Network Imaging and Modulation at Harvard University, and his team published a study in the journal Neurology where they used a modified magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) method to identify the brain network necessary for consciousness.

Trying to identify the anatomical basis for consciousness, an intractable phenomenon difficult to quantify and model, is not a new endeavor. “What was novel was our approach,” said David Fischer, first author of the study. “It centered around the idea that one way of getting at the neurobiology that supports consciousness is to look at where small lesions that disrupt it are located.”

To do so, Fischer and his team compared the brain activity of 12 patients with coma-causing lesions to that of 24 healthy individuals using strict clinical scores. They honed in on the brainstem, which is specifically affected by coma-causing lesions, and identified the part of this brain region that is critical for consciousness: the rostral dorsolateral pontine tegmentum.

Fischer used an imaging technique known as resting-state functional connectivity MRI to identify other parts of the brain that communicate with the rostral dorsolateral pontine tegmentum. “This technology had rarely been applied to the brainstem before,” said Fischer. “A really big challenge was getting reliable connectivity data to [this region], which is a small part of the brain that’s difficult to get signal from.”

After compiling data from a large group of patients, the team identified two cortical areas—the ventral anterior insula and the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex, both previously implicated in arousal and awareness—as actively communicating with the brainstem. Their findings define the brain network that supports consciousness with groundbreaking resolution.

“My hope is that people will be able to target this network clinically to help improve patients who suffer from disorders of consciousness,” shared Fischer. “Our study moves us a step closer to understanding how the brain produces consciousness, but I don’t have any illusions that it solves all the complicated problems with this topic. I hope it generates a lot of interesting questions and motivates future research.”