Exploring the future of fecal microbiota transplantations

Elizabeth Hohmann discusses her work with fecal microbiota transplantations (FMTs), how this field is developing and the expanding clinical potential for this treatment.

Please could you introduce yourself and provide a brief summary of your career to-date?

I’m an infectious disease physician at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH, MA, USA), where I’ve been since 1990. My expertise is in gastrointestinal infections so as part of that work I became interested in Clostridium difficile infection. Fecal transplants were coming into the lexicon for use in around 2011-12 and, essentially my 15 seconds of fame is, we demonstrated that a frozen inoculum, when administered from below by colonoscopy was basically the same as if you put it in from above using a nasogastric tube.

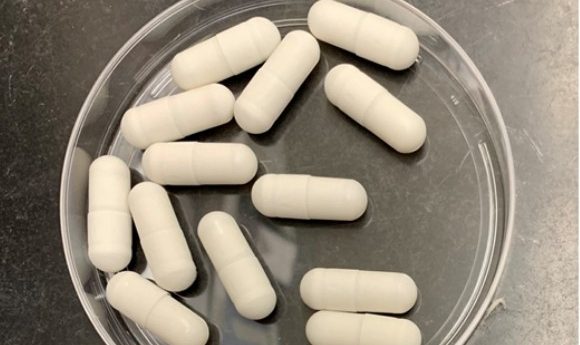

We did a small study to seeing if the cure rates were pretty much the same, which was in preparation for making frozen capsules that we would administer to people. In infectious diseases we don’t do any procedures, we just write prescriptions, so I was interested in being able to do this by capsule.

Since then we have treated over 400 patients with recurrent or refractory colitis with FMT capsules and it’s quite successful. Now we are moving into other potential applications in microbial manipulation and of course the great thing about capsules is that you can have a placebo that is totally distinguishable from the real thing. We now have a couple of studies ongoing in different areas; the bone marrow transplant area, which is what I was discussing at AACR and we also have a number of other studies in other applications as well.

What began your interest in fecal transplants?

The first reported cases in the USA were done in 1958. It was a bit of a ‘snigger’ thing in the 80s and 90s and so rarely done. In the 2000s I think people started to appreciate that there was an increasing number of people with recurrent and relapsing C. difficile colitis. What really pushed me to get into it was one of our trainees spoke about a case of a woman who had been admitted to the hospital 13 times for C. difficile colitis.

He explored and realized that nobody in the biggest hospital in New England, which was us, was doing this and we actually had to send this woman out to another smaller hospital in town for this procedure. It actually didn’t work for her so she ended up coming back and then we did it for her as well and it did work so that case was what got me into this. Thinking about some otherwise healthy person who had been admitted to the hospital 13 times was really a mind blower.

You recently presented at AACR, could you provide an overview of what you discussed and the key takeaways from the panel?

I reviewed the incapsulated work that we’ve been doing at MGH for a few years now. I guess there’s two interesting things from the cancer perspective, one is that a lot of cancer patients undergoing treatment do have perturbed microbiomes and they also have gastrointestinal symptoms.

A lot of antibiotics are used in cancer patients when their immune systems are suppressed by chemotherapy and so they end up having a high incidence of C. difficile infection but they also have a lot of diarrhea in general. The studies that we initially did in bone marrow transplant patients were really for safety and feasibility.

We enrolled 18 patients, we ended up treating 13 of them with fecal transplant after they’d been admitted to the hospital, gone through all their chemotherapy, reconstitution of their bone marrow with a transplant and then when that had re-engrafted we gave them a fecal transplant and showed that this was safe and feasible in this population. Now we have an open study were we’re doing it both before and after bone marrow transplant so on the patient’s way into the hospital for and on their way out of the hospital. This study is active right now and is a placebo controlled study.

What kind of clinical impact do you think research into this technique will bring, particularly for the cancer community?

I hope we’ll be able to significantly affect this patient population in a broader way because these people have often already been heavily treated for their leukemia or lymphoma typically, that didn’t work, so now they’re moving on now to another, more intensive treatment. I hope we’ll be able to show again that this is safe but also that there is a difference between the placebo and the active treatment and that we’re really impacting things like the incidence of infections and graft-vs-host disease.

It’s a small study so that’s kind of an optimistic claim but I do believe that this will be good for these patients overall, a, because they have a disordered microbiome to begin with, b, because they get tons of antibiotics when their immune systems are at their weakest and c, because there is increasing data that shows that your intestinal microbiome is at least correlated with, and we hope is causally related to, other outcomes like incidence of graft-vs-host disease, long term survival and possibly even response to specific therapeutic agents directed at their cancers particularly the immunotherapies that are all the rage in cancer now.

I think that is one of the most exciting things in cancer right now; all of these new immunotherapy targets which are essentially unleashing the immune system to attack cancers from within and if we can improve those response rates that would be a really big step forward. Immune-oncology is really exciting and I know that there’s a lot of companies looking at that and specifically trying to combine these new immunotherapies with microbial modulation for better outcomes.

What further advances do you envisage with respect to the use of fecal transplants in the coming years, potentially moving outside of cancer therapy and into areas such as neurology?

There probably isn’t a month that goes by that I don’t get somebody calling me up saying, hey I need fecal transplants for x, y, z, give it to me, and I say, well, thanks for your interest but I can’t do that because my program is under review of the US FDA and there’s very specific indications that we can treat.

I’m personally somewhat skeptical about neurological diseases because I think those are often chronic illnesses. There is some interest in diseases such as multiple sclerosis, which is an immune-mediated disease. We know that we could we make some headway in people who have their first episode or who are early in the disease, I think that makes more biological sense.

I have had enquiries from the ALS world and, again, there are correlations but I’m not sure there’s reason to believe there’s a causal effect there, there may be but it’s just too early to tell. I think we need to be quite cautious about new indications and where we go. C. difficile is sort of the easy target and it works astonishingly well for that but I’m not sure we can take those big steps at this time to other non-gastrointestinal illnesses.

Anything else to add?

I think fecal transplants are challenging from the regulatory perspective and there’s been a lot of arguments about this – is this a drug, is it an organ, what exactly is it? And it’s been a challenge for the overseers of the research community; both institutional review boards or ethics committees and also from the perspective of the US FDA. All in terms of how do we think about this and how do we screen, how do we insure that we’re doing this safely, what are the long term outcomes?

We had another study that’s under review now looking at obesity and metabolic syndrome. That is an area where there’s a lot of interest but also concern, can you take someone’s microbiome and change them into a skinny, healthy person from an obese person or vice versa.

Another great example of this is food allergy, specifically peanut allergies, so there’s microbiome therapeutics directed at that and I just think we need to exercise some caution particularly in younger people because if you are changing their microbiome when they’re 15 years old they may have 70 years to live with the consequences of that, a note of caution would be advisable.

Do you have a specific standing point on these debates? Would you say it’s a drug or an organ or are you just open to more research and seeing where it goes?

I don’t think it’s an organ because it is a mutable thing and it changes a lot. We put this microbiome into this person today but it can change a lot over time. The other important thing is that I don’t think we know how much we can change somebody’s microbiome just coming at it from the outside. This issue of how much of a clean slate or denuded forest do you need to have to put in a new microbiome.

Do you need to get rid of what’s there or put new stuff in? What will happen if you just put new stuff in? I think there’s a whole lot of science yet to be done there. I guess I’m thinking about it as a drug. The US FDA looks at it in a pretty balanced way right now and they think about live bacterial products and is it a single organism or multiple organisms. I think it’s a field that’s in evolution, it’s changing so quickly; a decade ago we didn’t know the word microbiome and now it’s one of the hottest words in science.