A tiny solution for plastic pollution: scientists discover polyurethane feeding bacteria

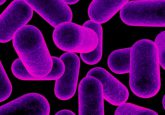

Scientists have identified a strain of bacteria that can feed on toxic polyurethane-based plastic products.

Since the 1950s, we have produced more than 8 billion tons of plastic, with the majority of this ending up in landfill or polluting the oceans. Now, German scientists have found a small solution to this big problem – plastic-eating bacteria.

This newly identified strain of Pseudomonas bacteria was discovered by a team consisting of researchers from Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (Leipzig, Germany), Freiberg University of Mining and Technology (Germany) and Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (Braunschweig, Germany), who have demonstrated its ability to break down polyurethane, a toxic type of plastic that is particularly hard to recycle.

In 2015 alone, polyurethane accounted for 3.5 million tons of the plastic produced in Europe. Its lightweight, insulating and flexible properties make it suitable for use in many products, from shoes and refrigerators to kitchen sponges. However, it’s incredibly difficult and energy-intensive to recycle, so most ends up on landfill sites where it releases toxic, often carcinogenic, chemicals.

Most bacteria are unable to withstand the toxic fumes released by the plastic, but, as demonstrated in a recent study published in Frontiers in Microbiology, this newly discovered strain is able to not only withstand and survive in the harsh environment, but also degrade some of the chemical building blocks of polyurethane and use these for energy.

With life science company Sartorius signing up to the European Plastics Pact, is replacing single-use plastics in the lab on the horizon at last?

“The bacteria can use these compounds as a sole source of carbon, nitrogen and energy,” remarked co-author of the study, Hermann Heipieper (Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research). “This finding represents an important step in being able to reuse hard-to-recycle [polyurethane] products.”

In order to test biological degradation of polyurethane, the team isolated a soil bacterium, Pseudomonas sp. TDA1, from a polyurethane-rich plastic waste site. They discovered that the bacteria could grow in a polyurethane-diol solution using the polyurethane precursor 2,4-diaminotoluene as its main source of energy.

They then performed a genomic analysis to uncover information about the degradation processes and revealed the presence of numerous catabolic genes for aromatic compounds. Further analyses were utilized to glean more information about the bacterium’s capabilities.

While this study has demonstrated huge potential in the use of biological degradation to reduce the amount of plastic waste, a lot more work is needed before the bacteria could be used on a wide scale. In fact, the team believes it could be upwards of 10 years before the bacteria could be used to make a difference.

“When you have huge amounts of plastic in the environment, that means there is a lot of carbon and there will be evolution to use this as food. Bacteria are there in huge numbers and their evolution is very fast. However, this certainly doesn’t mean that the work of microbiologists can lead to a complete solution,” Heipieper stressed. “The main message should be to avoid plastic being released into the environment in the first place.”

Europe takes on plastics

Europe takes on plastics