Characterizing metabolite messengers: how the gut and brain communicate

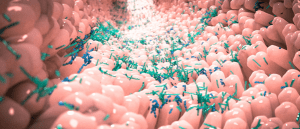

How do gut microbes communicate with the brain? A new study used a novel tool to characterize and evaluate the compounds that microbes produce, called metabolites, to find out.

A collaborative team led by researchers from Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital (both TX, USA) and the Medical University of South Carolina (SC, USA) provides a protocol for investigating metabolites in both in vitro and in vivo models. Metabolites are an important part of gut–brain communication, an axis that has been previously implicated in anxiety, obesity, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease. Although the last decade has seen an increase in gut–brain axis research, there is still a vast amount we don’t understand.

The brain- and micro-derived chemical signals involved in the communication between the gut and brain are complex and difficult to isolate, meaning that deciphering which microbial species is responsible for which brain alteration is a major challenge.

Could gut bacteria help us understand the causes of multiple sclerosis?

Could gut bacteria help us understand the causes of multiple sclerosis?

Research has shown that patients with multiple sclerosis have differences in their gut bacterial compared to healthy controls.

The current research team devised a protocol to gain insight into how a specific microbial species affects the gut and brain. First, they grew a specific microbe identified in the gut in culture. They then collected the metabolites produced by the microbe and analyzed them using targeted liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry-based metabolomics methods.

“The effect of metabolites was then studied in mini-guts, a laboratory model of human intestinal cells that retains properties of the small intestine and is physiologically active,” explained Melinda Engevik (Medical University of South Carolina), co-first author of the study. “In addition, the microbe’s metabolites can be studied in live animals.”

The team went on to examine how microbes and their metabolites affected intestinal organoid cultures and even mouse models, testing a range of environments to investigate how the different metabolites individually act as well as how communities of metabolites act.

The team is hopeful that this study will assist future researchers to create designer microbial communities that benefit the body and promote a healthy body and brain. They also highlight how their protocol can be used to identify potential solutions when gut–brain miscommunication causes disease.