Deinococcus radiodurans: A bacterium that might live on Mars and is more metal than you

There could be life on Mars. It could be pretty hardcore. It could be coming to earth. There is life on Earth. It could be going to Mars. Scientists frown.

You’re never going to be more metal than a tardigrade. Anything that can casually drift through the vacuum of space like it’s Sunday at the beach is automatically worth serious respect. But you’ve almost certainly got something like bacteria beat… right?

While we’ve long since abandoned the search for little green men or portals to hell on Mars, researchers at Northwestern University (IL, USA) are suggesting that life is possible on the red planet. What’s more, they’re tentatively flagging the possibility of microbial cross-contamination between our planet and Mars.

Prospective plans and missions to the fourth planet are under increasing focus from industrial interests, running at cross purposes to the scientific community, which holds the following two governing principles of protection:

The first is that spacecraft should not carry terrestrial biological materials that could compromise future studies. This aims to prevent forward contamination. The second is that Earth should be protected against the introduction of microorganisms returning from extra-terrestrial bodies. This aims to prevent backwards contamination.

This concern may seem slightly excessive given the fact that it is directed at a planet with a surface comprised largely of basalt rock covered in ferric oxide dust and an outer mantle of which roughly 18% is iron according to one 2004 estimate. Or considering the temperature, which averages a slightly nippy -63 degrees Celsius in the mid-latitudes. If that isn’t too much for you, try the unremitting bombardment of galactic cosmic radiation and solar protons. Which is to say that surviving on Mars is perhaps a bit beyond the survival capabilities of the average person. Or, indeed, the average anything. But as an esteemed philosopher once observed: “life, uh, finds a way.”

Previous studies had confirmed the veracity of this assertion, identifying a microbe nicknamed ‘Conan the Bacterium’ that could potentially survive on mars for 1 million years. In order to further explore the potential of life on Mars, scientists at Northwestern University have run a set of simulations to put the metal of Conan and other microbes to the test.

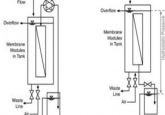

If there are bacteria present on Mars, they would have to be incredibly sturdy, capable of surviving close to the surface despite the inhospitable conditions. To assess the capability of existing microbes on earth to withstand these conditions, the researchers worked out the survival limits of microbial life to ionizing radiation. After this they exposed six forms of earth bacteria and fungi to the simulated conditions of a frozen and dry Martian environment, complete with gamma rays and protons to replicate radiation in space.

Microorganisms in a volcanic crater lake sheds light on life on Mars

Microorganisms in a volcanic crater lake sheds light on life on Mars

The biochemical capabilities of microorganisms from the Laguna Caliente, a hydrothermal crater lake, was studied using DNA sequencing and gives insight into how life on Mars could survive.

The outcome of these tests confirmed that it is, in fact, possible for a select few terrestrial microorganisms to survive a Martian climate over the course of hundreds of millions of years. Deinococcus radiodurans, the formal moniker of the previously noted ‘Conan’, is one such bacterium, shrugging off radiation and temperature, and outlasting Bacillus spores which are known to survive for millions of years here on earth.

It was impressive enough for Deinococcus radiodurans to last several hours on the surface while exposed to ultraviolet light. When buried just 10 cm below the surface, the survival period lasted a adequate 1.5 million years. When buried 10 meters below the surface, Deinococcus radiodurans could survive for a cool 280 million years.

To put that in terms that a human might have some vague hope of grasping, 280 million years is just shy of the span of the entire Paleozoic era, which was divided into six separate geologic periods. At the point where you’re measuring time in rock formations, it’s time to give up.

This titanic toughness is partially due to the genomic structure of the bacterium, with chromosomes and plasmids perfectly aligned and linked, making them repair-ready after a tanning session that would make Patrick Bateman blush. All of which means that if a microbe similar to this bacterium evolved during a period in which water flowed on the planet, then there is a possibility that its living remains could be resting, Cthulhu-like, deep below the surface of Mars.

The findings reinforce the idea that remnants of Martian life, if such a thing ever existed, could be uncovered by investigations by two future missions – ExoMars and the Mars Life Explorer, which will drill into the Martian soil and gather minerals from 2 meters below the surface – highlighting the risk of reverse contamination. The simulations also suggest that some strains of bacteria are capable of surviving the harsh environment of Mars, opening up the possibility that the planet itself could accidentally become contaminated by bacteria travelling with future astronauts and space tourists.