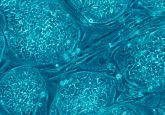

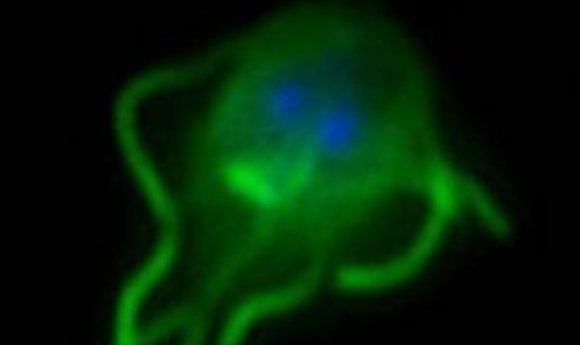

Giardia mimic human proteins to cause disease

How does the microscopic parasite giardia cause gut-wrenching gastrointestinal disease? By mimicking proteins important for tissue remodeling, says new research.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), giardiasis, a gastrointestinal illness known for its stomach cramps and diarrhea, is the most common intestinal parasitic disease affecting people in the United States today. It’s even more common in the developing world. While the microscopic protozoan parasite that causes giardiasis, giardia, has been studied since the 17th century, scientists have not been able to successfully explain how it causes its symptoms.

“Giardia is an interesting organism. Some people have it and get very ill. Others don’t get ill at all,” explained Kevin Tyler, a researcher at the University of East Anglia’s Norwich Medical School. “And if you look at the biopsies of people with giardiasis, occasionally you will see damage to the duodenum, a small part of the small intestine. But less than 10% of people who are very ill with the disease show that. In most people, the gut looks fine. How can we explain this?”

To see what might account for these differences, Tyler and colleagues used quantitative proteomic analysis of the parasite as well as the newest mass spectrometry platforms. They learned that the parasite secretes specialized proteins that mimic tenascins, a group of proteins critical for cell adhesion and tissue remodeling in humans.

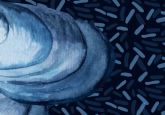

“We can now see vanishingly small traces of proteins with these new platforms. We were able to detect over 1600 proteins per Giardia. When we looked at the ratios in the media they were growing in, we could identify the ones that were being actively enriched by the media and those that were being secreted,” he reported. “We found only a very small number of small proteins were being secreted. They fell into two super families, for the most part—and one of those were like the tenascins, thought to be modulators of the extracellular matrix, which is responsible for holding our tissues together. Simply stated, the parasite has made a protein that essentially unsticks the cells of the gut lining so it can feed off of them.”

That “unsticking” can lead to the hallmark symptoms of giardiasis.

These proteins may offer a potential target for new drug therapies to treat giardiasis in the future. But Tyler cautions that there is still much to learn about these proteins and how they contribute to giardia-related illness.

“This could help us understand the difference between virulent and avirulent strains of disease. We think that by having identified these tenascins, we can learn something about the virulence from looking at different alleles in the genes that produce these proteins,” he said. “But there’s still quite a bit of work to do.”