Jumpy viruses

A new method shows how often viruses jump into new hosts. Will this predict the next pandemic?

From SARS to Ebola to Zika, diseases often emerge after viruses jump from animals into humans. Understanding which viruses are the best “jumpers” could help prevent pandemics, so Eddie Holmes at the University of Sydney in Australia and his team have developed a way to determine the “jumpiness” of viruses found in the wild.

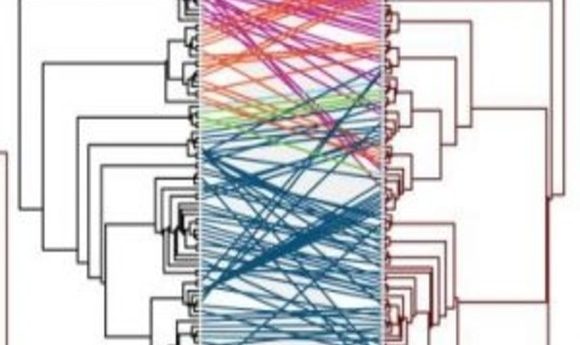

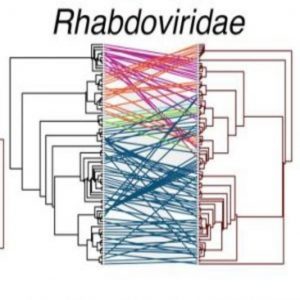

In a new study in PLoS Pathogens, Holmes and his team examined 19 families of RNA and DNA viruses and their eukaryotic amphibian, plant, mammalian, and insect hosts. They then did a comparative co-phylogenetic analysis using a normalized tree topology distance metric to look for congruence between the viral evolutionary tree and the animal evolutionary tree.

“We used this method as a way of quantifying in a rigorous way the mismatch between the evolutionary tree of the virus and the tree of the host,” said Holmes. “That then tells us the frequency with which the viruses can jump species.”

If the virus tagged along as its host speciated (i.e., they evolved together), the trees match. Mismatches indicate that the virus jumped at some point from a different host. The team hypothesized that, with genetic barriers, jumping would be a relatively rare occurrence. Surprisingly, they found just the opposite.

“I think the critical thing is that all virus families can jump between hosts,” said Holmes. “So although some viruses have been around for many, many millions of years, every family we found has the ability to jump hosts pretty frequently, some extremely so.”

Co-divergence was infrequent, though more common in viruses containing double-stranded DNA genomes. Notably, all the RNA viruses, especially Rhabdoviridae and Picornaviridae, showed many mismatches between the virus tree and the host tree, which means these viruses frequently jumped species.

Holmes opines that this work will, in fact, not help scientists predict which virus family will be most likely to emerge in humans, because they all jump. “Our absolute best bet is to have remarkably good surveillance,” he said. “The commonality in disease emergence is that it’s generally about humans interacting at the human–animal interface. So what I think you have to do is survey people very closely who work at that interface, who are being exposed to animals and the viruses they carry. Then act very quickly on that.”