Monkeypox: what we know

Cases of monkeypox have been rising in non-endemic countries around the world. In this article, we’ll explore what we already know about the disease.

Monkeypox is a rare zoonotic disease caused by the Monkeypox virus (MPXV), which infects various animals, including rats, different species of monkeys and humans. Monkeypox hit the headlines recently due to an ongoing outbreak in which over 100 cases have been reported across 19 countries, predominantly in Europe, since the beginning of May; but what do we know so far and how worried should we be?

Epidemiology

Monkeypox was first identified in lab monkeys in Copenhagen (Denmark) in 1958 – hence the name ‘monkeypox’ – and the first cases in humans were reported in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Since then, cases have been mostly limited to tropical rainforest regions in central and west Africa. Monkeypox incidence has been rising over the past decade, and there have been several small-scale outbreaks, the largest being in Nigeria, with over 500 suspected cases and 200 confirmed cases being reported since 2017.

MPXV

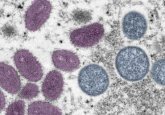

MPXV is an enveloped double-stranded DNA virus that belongs to a subset of the Poxviridae family of viruses called Orthopoxvirus, the same subset smallpox belongs to [1]. There are two main clades of MPXV – the Central African clade and the West African clade. Historically, the central African clade is thought to be more transmissible and results in more severe disease.

Researchers have already published a first draft genome sequence of the MPXV associated with the current outbreak, sequenced from a confirmed case in Portugal. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of the draft genome suggests that the virus belongs to the West African clade and is closely related to a case identified in the UK in 2018 in an individual that had recently traveled to Nigeria. This suggests that there are no novel mutations present in the currently circulating virus. The US CDC has published a draft sequence for a case identified in the USA, which appears similar to the Portuguese sequence. Sequencing experiments are ongoing, and we will undoubtedly see the release of new genome data, which will be vital to determining the origin and spread of the 2022 virus.

Transmission

MPXV can be transmitted both from animals to humans and between two humans [2]. This transmission typically results from contact with secretions of the lesions associated with monkeypox or via contact with large respiratory droplets [3]. Both key methods of transmission require close, prolonged contact with an infected individual, making human-to-human (H2H) transmission inefficient when compared with more transmissible diseases, such as COVID-19.

As a result of these inefficient transmission pathways, H2H spread usually occurs within households and can also be transmitted during sex. A 2014 review found that amongst household contacts unvaccinated against smallpox, 11.7% went on to develop the disease.

It has been noted that the clusters of infection observed so far contain a significant overrepresentation of men who have sex with men (MSM) when compared to the general population. This indicates that sexual transmission may be playing a key role in the spread of the disease and, alongside the aforementioned gene sequence that indicates that there are no novel mutations present in these infections, supports the theory that these outbreaks are circumstantial. There is no indication or implication that the disease is more transmissible among MSM, this fact simply highlights the role of sex and close contact in transmission.

You spin me right round: groups of malaria parasites form vortices

Researchers used computer simulations to identify the mechanisms behind the rotating vortices formed by groups of Plasmodium, malaria-causing parasites.

Infection biology

MPXV is known to have a wide-reaching host tropism and can infect many different species. This generality also translates into its cell and tissue tropisms; the virus has been found to infect tissues ranging from the heart and brain to the ovaries and lymphoid tissue [2].

Once inside the body, MPXV infects cells through a series of interactions between viral and cellular proteins, for instance the viral D8L protein, which binds to the cell surface receptor chondroitin sulfate. Once bound, the virus enters the cell by fusing with the cell membrane or by endocytosis [4]. In this manner, the virus can enter cells, replicate and then infiltrate the bloodstream, after which it can spread through the bloodstream to any of the many tissue types that it is capable of infecting.

Symptoms

As a close family member of the variola virus (smallpox), many of the symptoms of monkeypox mirror its cousin. The main difference is that during MPXV infection, lymph node enlargement is noticed at an early stage of the infection, typically as fever begins and headaches, coughing and sore throat are observed. This is followed by the appearance of a rash and smallpox-like lesions 1–3 days after fever onset [3]. The viral incubation period before symptom onset is between 7–21 days, so transmission for the cases we are seeing at the moment likely happened a few weeks ago.

Due to the wide tissue tropism of monkeypox, targeting the infection can be difficult and images of individuals severely infected with the disease display the characteristic lesions covering numerous locations. If an infected individual is able to overcome the disease, the symptoms typically last 2-4 weeks. However, monkeypox can prove fatal in roughly 10% of cases, with death occurring in the second week of infection [4].

Diagnosis and treatment

If a monkeypox case is suspected, a PCR test can be carried out to confirm the diagnosis. Like COVID-19, PCR tests are the preferred method of diagnosis due to their accuracy and sensitivity.

Monkeypox symptoms often resolve on their own, and care focuses on alleviating symptoms. No therapeutics have been developed for treating monkeypox specifically; however, due to the similarities between monkeypox and smallpox, treatments that were originally developed for smallpox could potentially be used to treat monkeypox. For example, tecovirimat is an antiviral with activity against smallpox, monkeypox and other orthopoxviruses. The drug is approved for treatment of smallpox in the USA and is approved for the treatment of both smallpox and monkeypox in the European Union, although it is not yet widely available.

Smallpox vaccination is around 85% effective at preventing monkeypox; however, since the official eradication of smallpox in 1980, smallpox vaccines are no longer available to the public. Experts have speculated that waning immunity from smallpox vaccination could be contributing to the rise in cases, as did a Review published in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, which warned of rising cases and the changing epidemiology of monkeypox [5].

What happens next?

Monkeypox is no COVID-19, and although with increased surveillance and testing we expect to see more cases in the coming days and weeks, the virus’s inefficient transmission will limit the spread. We will hopefully see more genomic data and analyses published, which will provide us with a better understanding of the 2022 MPXV and the current outbreak.

Unfortunately, deforestation and the climate crisis are forcing humans and animals into more contact, which increases the chance of zoonotic diseases spreading, so we need to be prepared for more zoonotic infections worldwide.