Selenomonas sputigena gets a plaque for aiding tooth decay

Researchers recently discovered that the bacteria Selenomonas sputigena (S. sputigena) forms a key partnership with Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) to cause tooth decay.

For years, it has been accepted that S. mutans is the bacterium responsible for forming plaques and producing acid that results in cavity formation and tooth decay. However, a new study, conducted by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine (PA, USA) and the University of North Carolina (NC, USA), has found that S. sputigena, a bacteria implicated in gum disease, may also play a crucial role in the process.

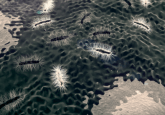

Cavities, also known as caries, are the most common chronic disease among children and adults in the United States and around the world. People develop cavities when acid-producing bacteria, such as S. mutans, build up on and around the teeth due to poor oral hygiene. These bacteria form a biofilm or ‘plaque’ that converts sugars in the diet into acids that eventually, if left too long, break down the affected tooth’s enamel.

Previous studies have found other bacterial species involved in tooth decay, but the current study is the first to implicate S. sputigena, an anaerobic mobile bacterium found in diseased gums, in cavity formation.

Superorganism identified that can ‘leap’ from tooth to tooth

Superorganism identified that can ‘leap’ from tooth to tooth

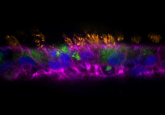

This study finds evidence of multi-cellular cross-kingdom superstructures that can move from tooth to tooth, causing more extensive tooth decay.

In this study, the researchers sampled plaque from the teeth of 300 children between the ages of 3 and 5 years old, half of whom had cavities. The team analyzed these samples for bacterial gene activity and their biological pathways using a variety of techniques, such as multiomic analyses, computational imaging and virulence assays.

The results showed that S. sputigena cannot cause cavities on its own and acts as just one of many bacterial species that cause caries. S. sputigena works together with S. mutans to boost tooth decay. It does so by getting caught in the glucans, sticky constructions within plaque made by S. mutans, and proliferating rapidly to produce superstructures that protect S. mutans. This added layer of protection allows for increased acid production and cavity severity.

Understanding this complex microbial interaction could provide insight into how cavities develop in children and how we can better prevent them. “Disrupting these protective S. sputigena superstructures using specific enzymes or more precise and effective methods of tooth-brushing could be one approach,” suggested senior author Hyun Koo (University of North Carolina).

In the future, the team plans to investigate how S. sputigena actually ends up on the tooth surface, given that it shouldn’t want to exist in an aerobic environment like that. “This phenomenon in which a bacterium from one type of environment moves into a new environment and interacts with the bacteria living there, building these remarkable superstructures, should be of broad interest to microbiologists,” commented Koo.