The bodies of medieval friars were far from temples

Archaeologists find that medieval friars had a higher rate of parasitic infections than the average population.

In the days before modern medicine, life was tough for nearly everyone. European medieval history is notorious for bad hygiene and rampant disease that engulfed entire towns, countries and continents. In the hierarchy of medieval society, the clergy were typically second only to nobility and typically enjoyed better conditions, diets and lived longer than the peasant class.

However, a new study from the University of Cambridge (UK) has revealed that the grass may have not been greener for the friars. Findings from a new excavation have revealed that the filthy friars had nearly double the rate of intestinal parasites as the general population at the time.

The remains of 19 friars found at the ruined Augustinian Friary in Cambridge had samples of their pelvic sediment taken and analyzed for evidence of parasitic eggs. The researchers found parasitic eggs in 11 of the friars (58%), compared to only 8 (32%) of the non-ecclesiastical pelvises analyzed in the same study, retrieved from a nearby gravesite. The team used micro-sieving and digital light microscopy to probe for the eggs.

“Finding a significant difference in the proportion of people infected by parasites was quite a surprise,” said lead author Piers Mitchell.

Acetates: the new culprit for alcohol-related gut bacterial growth

Acetates: the new culprit for alcohol-related gut bacterial growth

Metabolites of ethanol have been found to be responsible for the overgrowth of gut bacteria displayed in patients with alcohol liver disease.

The friars were identified for the study by a tell-tale item they were buried with, as co-author Craig Cessford explained, “the friars were buried wearing the belts they wore as standard clothing of the order, and we could see the metal buckles at excavation”.

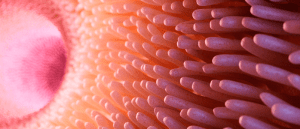

All the friars who tested positive for parasites were found to have roundworm, and one particularly unlucky friar also had whipworm. “The friars of medieval Cambridge appear to have been riddled with parasites,” commented Mitchell.

Both roundworm and whipworm spread through poor sanitation and not the consumption of undercooked meat or fish, which is the case for other parasites, such as tapeworms. Fundamentally, the root cause of this difference in infections must have been a difference in how the monks handled their waste. Whilst the general population was forced to use communal cesspit toilets, the sanitation systems of monasteries were developed, and many had running water.

Mitchell suggested one theory to explain why the scholars of Christ were so plagued by parasites; that it was the improved diet of the friars that was causing the parasites. “One possibility is that the friars manured their vegetable garden with human feces, not unusual in the medieval period, and this may have led to repeated infection with the worms.”

Interestingly, people at the time of the monastery were aware of parasitic worms. This was revealed in the writings of physician John Stockton, who donated his works to Peterhouse College (Cambridge, UK) upon his death in 1361. Stockton believed that phlegm was the source of worm infections and different worms were bred from different phlegms. “Long round worms form from an excess of salt phlegm, short round worms from sour phlegm, while short and broad worms come from natural or sweet phlegm,” noted Stockton, recommending aloe and wormwood mixed with honey as a cure.