Trust your gut… even when it’s synthetic

Researchers have constructed the most complete synthetic microbiome yet.

A team of researchers from Stanford University (CA, USA) has successfully transplanted a synthetic microbiome into mice, containing more than 100 specially selected bacterial strains. This development in synthetic microbiome modeling has the potential to aid in the creation of novel microbiome therapies.

Previous research has shown just how important a healthy gut microbiome is to processes situated in other parts of the body. A connection has been drawn between the bacteria in the digestive system and processes such as neural development and the body’s reaction to cancer immunotherapies. Therefore, being able to break down the gut microbiome to study isolated bacterial strains or how specific strains interact is an important step in understanding the role of the gut microbiome in disease.

Although fecal transplants have been utilized to study the microbiome, there aren’t tools available to modify, remove or add individual strains of bacteria. A synthetic microbiome that allows for editing and evaluation would provide the microbiome manipulation necessary to investigate which gut bacteria affect disease development and health. “So much of what we know about biology, we wouldn’t know if it weren’t for the ability to manipulate complex biological systems piecewise,” commented corresponding author Michael Fischbach.

What makes a house, a home? A new study suggests that it’s the roommates you share it with, both human and microbial.

The researchers were tasked with designing a stable and balanced microbiome, containing bacteria that complimented each other to carry out the functions of a natural gut microbiome. They began by curating a collection of prevalent bacteria from data provided by the Human Microbiome Project (HMP), a project sequencing and characterizing the full microbiomes of healthy adults. Fischbach reported, “we were looking for the Noah’s Ark of bacterial species in the human gut, trying to find the ones that were almost always there in any individual.”

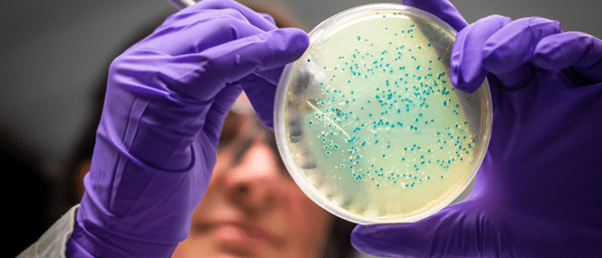

Selecting the bacteria present in 20% of individuals, according to the HMP data, the team grew 104 bacterial species separately before mixing them in one culture; this culture was called human community one (hCom1). They transplanted hCom1 into mice with no gut bacteria to test whether the synthetic microbiome would be effective in vivo. This first introduction of hCom1 was successful, populating the gut at constant abundance levels after two months.

To test the synthetic microbiome’s ability to function authentically, the researchers utilized colonization resistance, a theory that states that a foreign bacterium will only survive in an existing colony if it can fulfill a role that isn’t already filled by another bacterium. They introduced a fecal sample, which is an entire, natural microbiome, to their synthetic microbiome to see which bacteria were taken up by the synthetic microbiome in the hopes of creating a more robust, complete microbiome.

The natural microbiome didn’t overpower the synthetic one, contrary to many people’s predictions. In fact, hCom1 took up only 10% of its cells from the fecal sample. By adding the new bacteria gleaned from the fecal sample trials and removing the bacteria that was unnecessary in the first round of mouse trials, the team curated a final microbiome composed of 119 bacterial strains, called hCom2. When transplanted into germ-free mice, hCom2 was even more successful than hCom1.

The last test was to introduce Escherichia coli to mice colonized with hCom2; these mice were just as resistant to infection as those with natural microbiomes. The researchers can now edit hCom2 to determine which bacteria are responsible for protection, which is an ongoing effort.

Further research using hCom2 and more refined versions of it has the potential to offer insight into immunotherapy responses as well as the development of microbiome therapies.