Vampiric ‘satellite’ viruses attach to ‘helper’ viruses at the neck

Researchers identify the first known instance of one virus attaching to another with stunning clarity in transmission electron microscopy images.

Universities around the world run investigative modules where undergraduates can put their lab skills to the test in an attempt to identify novel interactions, molecules or species. These modules provide learning opportunities for students to get hands-on experience using techniques they’ve learned about; however, the likelihood of making a groundbreaking discovery is low. Having spent 6 months attempting to detect novel binding proteins for ubiquitin, potentially one of the most well-studied proteins in the life sciences, I found that although initially exciting, the constant cycle of hope and disappointment for each attempt can become rather disheartening.

This has not proved to be the case, however, for a group of undergraduates analyzing bacteriophages in environmental samples as part of the SEA-PHAGES program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC; MD, USA). On receiving their sequencing results from a lab at the University of Pittsburgh (PA, USA) and conducting a bioinformatic analysis, the team spotted a strange source of contamination. Alongside a large genome sequence that belonged to an expected phage, they also found a small sequence that didn’t correlate to anything in their database.

Genetic elements that hijack bacterial viruses contribute to the spread of antibiotic resistance

Genetic elements that hijack bacterial viruses contribute to the spread of antibiotic resistance

A newly revealed mechanism of horizontal gene transfer improves understanding of how antibiotic resistance is transferred between bacteria.

The team considered that perhaps the smaller sequence could represent a satellite virus: a type of virus that requires both a host cell and a helper virus, which provide either the facilities to produce its capsid or to replicate its DNA, for it to reproduce. For these satellite–helper relationships to function, they must be in proximity to one another.

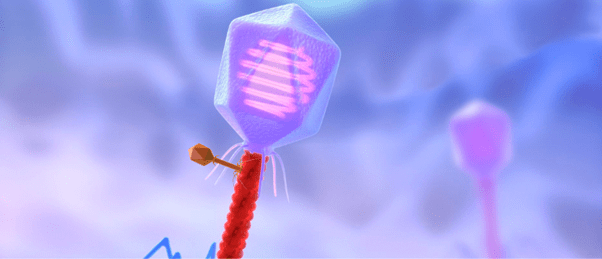

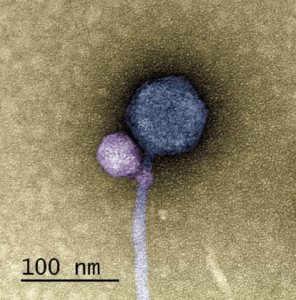

A colorized image of the newly discovered satellite virus latched onto its helper virus. Credit: Tagide deCarvalho.

To determine the nature of the smaller sequence, the team sent some of their sample to Tagide deCarvalho (UMBC), first author of the paper, who utilized transmission electron microscopy to obtain detailed images. These images revealed that in 80% of cases, the expected virus coded for by the large sequence, here-on referred to as the ‘helper’ virus, was bound at the neck by a smaller satellite virus (left). The remaining 20% of unhitched helper viruses had tendrils from satellite viruses still present at the neck, referred to by senior author Ivan Erill (UMBC) as “bite marks.”

“When I saw it, I was like, I can’t believe this. No one has ever seen a bacteriophage – or any other virus – attach to another virus,” remarked deCarvalho, recalling the moment she first examined the images.

Further bioinformatic and genetic analyses revealed that the satellite virus, which the team dubbed MiniFlayer, contained no gene for genetic integration into the host genome, a unique occurrence and one that makes MiniFlayer entirely dependent on the helper virus, which they named MindFlayer. “Attaching now made total sense,” Erill explained, “because otherwise, how are you going to guarantee that you are going to enter into the cell at the same time?”

Furthermore, the bioinformatic analysis revealed that the two viruses had evolved together over at least 100 million years, indicating that there could be further instances of this relationship that have yet to be discovered. These findings have wide-ranging implications, not just for our understanding of virology, but also for explaining challenging contamination issues with bacteriophage samples. “It’s possible that a lot of the bacteriophages that people thought were contaminated were actually these satellite–helper systems. So now, with this paper, people might be able to recognize more of these systems,” commented deCarvalho.