Zika virus, immunosuppression, and pregnancy

New research shows that immune cells are the initial target for Zika virus infection, resulting in immunosuppression. What new insight does this give us into the role Zika virus plays in fetal brain malformations?

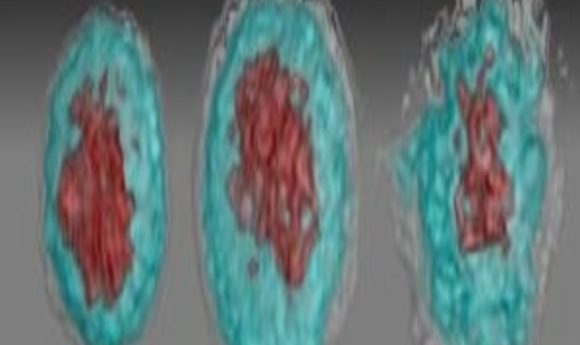

Images of Zika virus–infected white blood cells: left, healthy; middle, African Zika virus infected; right, Asian Zika virus infected.

Credit: Suan-Sin Foo, Weiqiang Chen and Jae Jung

Perhaps the only reason you’re aware of the 2015–2016 Zika virus epidemic in the Americas is because of its frightening link to microcephaly and other central nervous system malformations in babies born to mothers infected with the virus while pregnant. By early 2016, the situation was so alarming that the governments of several South American and Caribbean countries recommended that women postpone getting pregnant until more was known about the effects of the virus on fetal development.

First isolated in 1947 from a monkey in Uganda and later detected in humans in Africa and Asia, Zika virus had previously been known to induce only mild, non-life-threatening symptoms in a minority of infected individuals; the rest of the infections were asymptomatic. So, its recent emergence as the cause of fetal brain malformations was both unexpected and extremely puzzling. Now, a new study published in Nature Microbiology by researchers at the Keck School of Medicine in Los Angeles shows that the path to Zika’s devastating effects on the fetal brain begins with natural alterations in the mother’s immune response.

“Pregnant women are more susceptible to Zika virus because pregnancy naturally suppresses a woman’s immune system so her body doesn’t reject the fetus—essentially it’s a foreign object,” said senior author Jae Jung in a press release.

Jung and his colleagues used an in vitro whole-blood infection model, flow cytometry analysis, and gene expression profiling to determine that the virus initially targets CD14+ monocytes during the acute phase of infection. Interestingly, they found that the two known Zika virus lineages triggered different immune responses. The original African lineage induced classical/intermediate monocyte-mediated inflammation, while the Asian lineage responsible for the recent epidemics induced non-classical monocyte-mediated immunosuppression.

When the researchers infected whole blood from healthy pregnant women with Zika virus, they observed a higher viral load compared to non-pregnant controls and significantly stronger virus-induced immunosuppression in blood obtained during the first or second trimester of pregnancy. “During pregnancy, the host body is prone to opportunistic infection,” said Suan-Sin Foo, first author of the study. “With the help of pregnant women’s naturally weaker immune system, it’s possible for the Asian Zika virus to sneak into the womb and prey on the vulnerable baby.”

The authors also demonstrated upregulation of biological markers associated with pregnancy complications, including cytokines and fibronectin-1, both in the whole-blood infection model and in sera from Zika-infected pregnant women.

In addition to providing new insight into how Zika virus infects humans and the increased vulnerability of pregnant women and their fetuses, the current findings have immediate implications for efforts to prevent new infections. “The Zika virus vaccines in development seem to be highly effective, but they’re being tested among non-pregnant women with different body chemistry compared to pregnant women,” Jung said. “It’s feasible the recommended vaccine dose—though effective for non-pregnant women—may not be potent enough for pregnant women because their bodies are more tolerant of viruses.”