Predict the future before you forget the past

A newly developed early alzheimer’s test can detect Alzheimer’s in its preclinical stage, before the onset of cognitive symptoms.

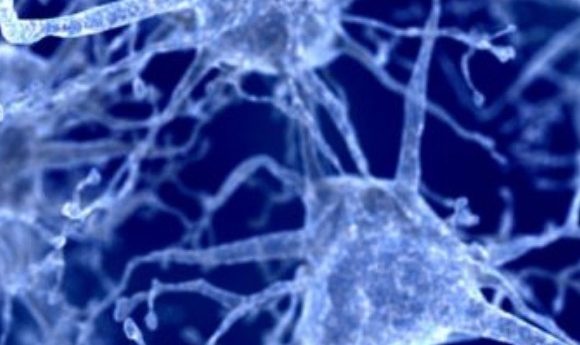

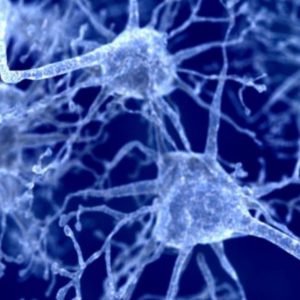

One of the key reasons as to why there is no effective treatment for Alzheimer’s disease is that all treatments start too late. By the time clinical symptoms occur there has already been significant brain damage and irreversible neuronal loss.

There has been some success previously in diagnostic blood tests for Alzheimer’s with focus on the levels of the amyloid protein that is characteristic of the disease. However, with controversy regarding the true effect of amyloid and its exact role in neurodegeneration unknown, this too may be detecting the disease at too late a stage.

Researchers from the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE; Bonn, Germany) have developed a new test, created from a different perspective.

“Our blood test does not look at the amyloid, but at what it does in the brain, namely neurodegeneration. In other words, we look at the death of neurons,” explained Mathias Jucker, a senior researcher from the DZNE.

Once released following neuronal apoptosis, protein fragments from inside the cell enter the bloodstream where they have the potential to be detected.

“Normally, however, such proteins are rapidly degraded in the blood and are therefore not very suitable as markers for a neurodegenerative disease,” continued Jucker; “an exception, however, is a small piece of so-called neurofilament that is surprisingly resistant to this degradation.”

With a blood test to detect this protein, the researchers found that the neurofilament can be found in the blood in the preclinical stage of the disease, long before the development of memory impairment and other such clinical symptoms. The level of the protein in the blood reflects the stage of the disease and allows for predictions of how it will progress.

Using samples from an international research collaboration, currently investigating early-onset Alzheimer’s and its genetic, familial basis, Jucker and colleagues monitored the neurofilament concentration in the individuals from year to year. The results, recently published in Nature Medicine, found that changes in the blood were observable up to 16 years before the onset of clinical symptoms. Changes in neurofilament concentration were able to accurately reflect neuronal damage and could predict loss of brain volume and cognitive changes up to 2 years before they would occur.

“It is not the absolute neurofilament concentration, but its temporal evolution, which is meaningful and allows predictions about the future progression of the disease,” commented Jucker; “we were able to predict loss of brain mass and cognitive changes that actually occurred two years later.”

The results also support the opposition to the amyloid hypothesis, a lack of correlation between neurodegeneration and amyloid concentration suggests that they are independent events. This demonstrates that the presence of amyloid may not be as causal as previously believed.

“The test accurately shows the course of the disease and is therefore a powerful instrument for investigating novel Alzheimer’s therapies in clinical trials,” concluded Jucker.