Testing for tau: a new blood test for Alzheimer’s disease

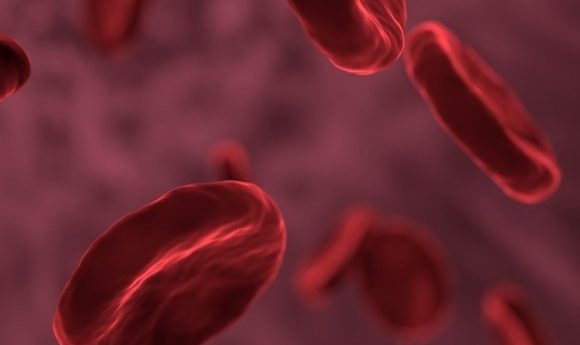

New blood test for Alzheimer’s disease, the tau protein may revolutionize the diagnosis of the disease and potentially predict its development.

Currently, an Alzheimer’s diagnosis is often the result of brain scans, invasive lumbar puncture procedures and a differential diagnosis. However, researchers from Brigham and Women’s Hospital (MA, USA) are working towards developing a simple blood test that can accurately diagnose the disorder and potentially predict its development before symptoms become apparent.

The tau protein is known to be a key part of Alzheimer’s pathology with hyperphosphorylation of the protein leading to its aggregation into neurotoxic neurofibrillary tangles. These tangles are believed to be important factors in the initiation of the extreme neurodegeneration associated with dementia.

The aim of the Brigham team’s research, recently published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia, is to utilize the complexity of this protein. There are many subsets of tau protein, only some of which are shown to be elevated in Alzheimer’s. In developing tests capable of detecting fragments of tau in the blood stream, the researchers found one fragment that showed significant specificity and sensitivity to allow it to be used as a diagnostic test for Alzheimer’s.

“A blood test for Alzheimer’s disease could be administered easily and repeatedly, with patients going to their primary care office rather than having to go into a hospital,” commented corresponding author Dominic Walsh. “Ultimately, a blood-based test could replace cerebrospinal fluid testing and/or brain imaging. Our new test has the potential to do just that. Our test will need further validation in many more people, but if it performs as in the initial two cohorts, it would be a transformative breakthrough.”

Assays targeting five different tau protein subtypes were applied to both plasma and cerebrospinal fluid that had been donated by participants from the Harvard Aging Brain Study as well as those from the Institute of Neurology (London, UK). The NT1 assay proved itself as the most accurate as results were confirmed in both sets of patients.

The researchers acknowledge that the study only had a small number in each population group and therefore to give further confirmation larger study groups would be necessary. They are also intending to perform a longitudinal study, observing patients over time in order to determine how levels of tau change over the course of the disease and estimate what levels would be like before the onset of symptoms.

“We’ve made our data and the tools needed to perform our test widely available because we want other research groups to put this to test,” Walsh added. “It’s important for others to validate our findings so that we can be certain this test will work across different populations.”