Want more out of exercising? Try changing your workout schedule

Exercise and sleep are vital to a healthy lifestyle, but researchers have just discovered that sleep schedules influence physical endurance and whether exercise burns sugar or fat.

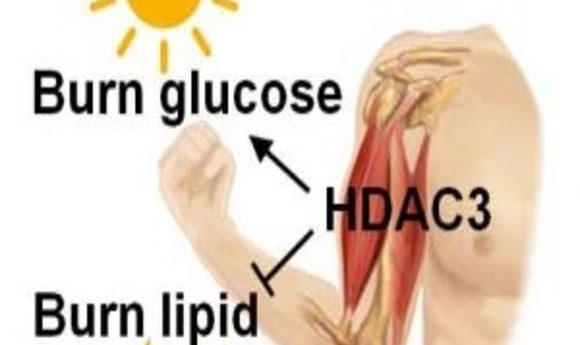

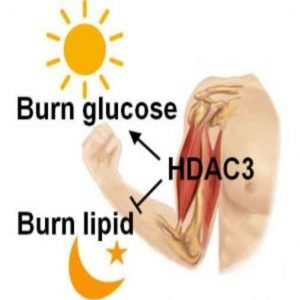

HDAC3 binding according to circadian rhythm regulates the use of glucose or lipid as muscle fuel and impacts exercise endurance.

If exercising is on your list of resolutions this year, changing the time of day you work out may increase your stamina and help you burn more fat according to a recent study in Nature Medicine(1).

Your biological clock, or circadian rhythm, dictates behaviors including eating and sleeping. At a molecular level, genes controlling metabolism are rhythmically transcribed in tissues such as the liver and skeletal muscle in alignment with circadianbehaviors. Now, a team led by Zheng Sun at Baylor College of Medicine and Mitchell Lazar at the University of Pennsylvania has shown how the circadian clock affects exercise endurance by determining the type of fuel our muscles use at different times of the day.

In 2011, Zheng found that the circadian clock regulates histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3), a DNA-modifying enzyme, to ensure that fat and glucose are not synthesized simultaneously in the liver (2). He then wondered if HDAC3 determines fuel metabolism in other tissues. “At the other end of metabolism are catabolic processes, that is, burning fuel—burning lipids, burning glucose—and that mainly happens in muscle,” said Zheng.

Zheng’s team created a knockout mouse with depleted HDAC3 in muscle tissue to study the influence of HDAC3 on muscle fuel metabolism. Muscles without HDAC3 had impaired insulin sensitivity and reduced glucose uptake during exercise, both indicators of type 2 diabetes. Interestingly, despite using less glucose, the knockout mice ran for longer periods of time on a treadmill. “That’s surprising,” remarked Zheng. “Usually diabetes and athletic endurance don’t go together.”

Indirect calorimetry analysis revealed that muscles without HDAC3 burned lipids rather than glucose as fuel, explaining the increased endurance of diabetic mice since lipid fuel lasts longer than glucose during exercise. Furthermore, direct lipid oxidation measurements showed that HDAC3 knockout mice burned more fat while exercising. To find out what made these mice burn fat, the researchers turned to metabolomics and unexpectedly identified amino acid catabolism as the driving force behind the fuel switch from glucose to lipids.

Since the circadian clock regulates HDAC3 in the liver, the team measured HDAC3 binding throughout the day with ChIP-Seq and found that binding peaked at dusk. Additionally, Rev-erbα, a key component of the circadian clock, controlled HDAC3 binding, confirming circadian control of muscle fuel metabolism through HDAC3.

Although a glucose-to-lipid switch for fuel likely evolved to ensure that the brain and red blood cells have an adequate glucose supply during sleep and fasting, humans may be able to harness muscle fuel metabolism to maximize exercise benefits. Light exercise at night while fasting may be more efficient to burn fat than exercising during the day while fed, according to Zheng.

In fact, lifestyle adjustments to fit our circadian rhythms may extend beyond HDAC3, according to Joseph Bass at Northwestern University, who was not associated with this study. “It’s an early time for this work but an exciting possibility that these types of adjustments, so to speak, can be made to…optimize different physiological functions,” he said.