Cilia say what? Important function of neurons’ tiny hairs

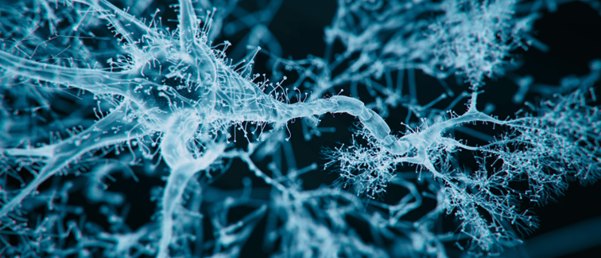

Researchers have uncovered a synapse on neurons’ tiny hair-like structures, which may facilitate long-term changes to genomic information in the nucleus.

A new study from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Janelia Research Campus (MD, USA) has identified special junctions on primary cilia, tiny hair-like organelles on the surface of neurons. These junctions provide a more direct, faster way to transmit information, like alterations to chromatin, to the neuron’s nucleus. This has potential for long-term effects facilitated by synapses on cilia provides an insight into an aspect of neuronal communication previously unexplored.

Traditional synapses, formed between an axon of one neuron and the dendrites of others, are well-characterized. However, a synapse between an axon and a cilium has not been observed until now. Interestingly, cilia are present on almost every type of cell, which makes sense during development as cilia are necessary for cell division because of their signal-detecting receptors. Later in life, cilia are important for proper lung function and sperm fitness. However, it is less clear why we maintain these protrusions on every cell into adulthood.

Mostly ignored until now, cilia have only just started being the center of scientific exploration thanks to improved imaging technologies. First author Shu-Hsien Sheu led the charge in the Janelia Research Campus, investigating cilia in brain tissue to understand their function. He used focused ion beam-scanning electron microscopy to visualize these structures.

No, we don’t have a ‘lizard brain’

No, we don’t have a ‘lizard brain’

Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research used comparative single-cell transcriptomics to study vertebrate brain evolution and put the idea of a ‘lizard brain’ to rest.

Sheu and his fellow researchers discovered the synaptic connections present between the cilium on the neuron’s soma (cell body) and the neuron’s axon. Upon further examination, the team found that these connections resembled traditional synapses. The next step was to understand the function of these axo-ciliary synapses.

Novel biosensors were designed and utilized in conjunction with fluorescence lifetime imaging to measure the biochemical characteristics and changes within the cilia. This revealed how axons release serotonin onto ciliary receptors, triggering a cascade of chemical reactions that signal chromatin opening and genomic changes in the nucleus. Therefore, the signal passed through the axo-ciliary synapse likely produces long-term, important effects.

Senior author David Clapham commented: “This special synapse represents a way to change what is being transcribed or made in the nucleus, and that changes whole programs. It is like a new dock on a cell that gives express access to chromatin changes, and that is very important because chromatin changes so many aspects of the cell.”

The current study specifically examined serotonin receptors, but there are numerous other types of receptors on cilia that require more research. This study has revealed the potentially important role of cilia in other parts of the body, such as on the liver and kidneys. Further investigation of these neuronal cilia and their axo-ciliary synapses could assist in the development of more targeted, selective medications.