Could gut bacteria help us understand the causes of multiple sclerosis?

Refer a colleague

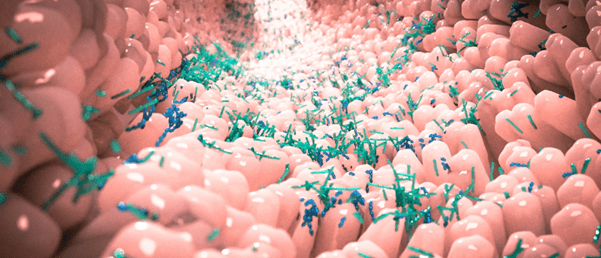

Research shows changes in the gut bacteria of multiple sclerosis patients compared with healthy controls. There are also microbiota differences between multiple sclerosis activity states.

Researchers led by Oluf Borbye Pedersen at the University of Copenhagen (Denmark) have identified that people with multiple sclerosis (MS) have different gut bacteria compared to healthy people. The study also found that MS patients have differing intestinal microbiomes depending on their disease activity.

MS is a chronic autoimmune disease of the central nervous system that results in physical and cognitive impairments. It is most frequently diagnosed in young adults in their 20s and 30s, but the underlying causes are not well understood. MS patients may have relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, characterized by periods without disease activity followed by a relapse that may cause further impairments.

The current case-controlled study compared the gut microbiomes of 148 Danish multiple sclerosis patients with the same number of healthy control subjects. Each participant provided blood and fecal samples when the study began and two years later. The scientists genetically analyzed the composition of the collected gut bacteria to assess their effect. They also measured the levels of known inflammatory markers in the blood plasma samples.

Composition of gut microbiome drives granulopoiesis

Composition of gut microbiome drives granulopoiesis

Researchers demonstrate that changes in the intestinal microbiome stimulate neutrophil production in mice.

The team identified 61 gut bacteria species that were differentially abundant when comparing all the MS patients with the healthy controls. This included 31 species that were enriched in patients with the disease. Researchers also identified clusters of inflammation markers that were positively associated with a group of disease-associated bacteria.

Finn Sellebjerg, a clinical professor and study co-author, explained that “undergoing treatment for multiple sclerosis seems to be linked to a change in the composition of bacteria compared with patients who are not undergoing treatment.” He added that some of the gut bacteria changes can be identifiably linked to the occurrence of inflammatory reactions in the body.

The researchers were most interested in the finding that there are two species of ‘good’ gut bacteria that are found more frequently in MS patients without active disease. These health-promoting bacteria produce fatty acids that the body cannot synthesize itself and anti-inflammatory metabolites, including urolithin.

Pedersen, the senior author, believes that this finding, if independently confirmed, offers a route to treatment trials. This could include an “anti-inflammatory, green diet and a cocktail of next-generation probiotics” to regulate immune competence. He cautioned that “unfortunately, there is still some way to go before we can provide specific advice on a health-enhancing lifestyle or bacteria supplement.”

Sellebjerg suggested that this research provides “a handful more pieces in the 10,000-piece jigsaw puzzle of multiple sclerosis, but there are still large gaps.” He added that, “the great difference is that the pieces we have found are starting to reveal systems that we can manipulate without the side effects some medicines can have.”

Please enter your username and password below, if you are not yet a member of BioTechniques remember you can register for free.