Mice can learn to reward themselves by using spontaneous dopamine impulses

The neurological messenger in the brain – the ‘feel good’ chemical – dopamine, is closely related to reward and pleasure reactions in people, but it has other random impulses too.

The versatile neurological messenger works by carrying signals between brain cells and it is involved in many processes in the brain.

Traditionally, the chemical has been studied from the point of view of external or ‘deterministic’ stimuli, but in this study from the University of California San Diego (CA, USA) the researchers aimed to investigate the spontaneous impulses of dopamine.

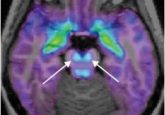

When examining the concentration of dopamine in mice brains the researchers found that not only does dopamine flood the brain in response to pleasure and reward-based stimuli as expected, but the chemical is also released with unpredictable impulses every minute.

Conrad Foo, from UC San Diego and first author on the paper, built on these results by testing whether the mice were aware of these impulse releases using molecular and optical imaging techniques. A feedback loop whereby mice running on a treadmill were given a reward if they exhibited control over the spontaneous dopamine signals was developed. The results, published in Current Biology, demonstrated that the mice were aware of the impulses and could even anticipate and act on a proportion of them.

Bring on festival season: why our brains like music

Bring on festival season: why our brains like music

New research published in the Journal of Neuroscience, details how communication between the brain’s auditory circuits and reward center leads to this feeling of musical pleasure in humans.

“Critically, mice learned to reliably elicit (dopamine) impulses prior to receiving a reward,” the researchers noted. “These effects reversed when the reward was removed. We posit that spontaneous dopamine impulses may serve as a salient cognitive event in behavioral planning.”

The research could have implications for gaining a greater understanding of drivers of behavior, the team believe. By elucidating such brain dynamics, we can see the role dopamine – and especially these impromptu releases of dopamine – plays in behaviors such as foraging, seeking mates and colonizing new homes.

“We further conjecture that an animal’s sense of spontaneous dopamine impulses may motivate it to search and forage in the absence of known reward-predictive stimuli,” the researchers stated.

The team realized that dopamine appeared to boost motor behaviors, rather than initiate it, but this could be used to motivate these social experiences to gain rewards.

“This started as a serendipitous finding by a talented, and curious, graduate student with intellectual support from a wonderful group of colleagues,” commented study senior co-author David Kleinfeld (UC San Diego). “As an unanticipated result, we spent many long days expanding on the original study and of course performing control experiments to verify the claims. These led to the current conclusions.”